My Country Is No Longer a Place - It’s an Argument

Being Venezuelan now means explaining yourself before you are even asked. I often find myself elaborating on my political experience and beliefs as fast as I said my name.

Although this experience is relatable to most Venezuelans, my position is further complicated because, unlike many, I'm critical of US foreign policy. This makes me feel like a constant outsider both among foreigners and among my fellow Venezuelans.

A photograph from the 2002 coup against former president Hugo Chávez, displayed at “El Cuartel de la Montaña,” a museum dedicated to his life and the site where his remains are kept. (All photos courtesy of the author.)

Perhaps the most troubling consequence of chavismo is that it stripped us of our ability to analyze conflicts and think clearly. In a country with a long history of leftist governments, a large portion of the Venezuelan population now feels not only celebratory but relieved by US intervention, even embracing it as a form of salvation. It seems we have lost the ability to resist simplistic readings of reality, sliding instead into a binary logic: my enemy’s enemy is my friend.

A street shrine dedicated to Hugo Chávez in Caracas’s 23 de Enero neighborhood, located across from "El Cuartel de la Montaña" where his remains are kept.

The greatest danger of this kind of reductive thinking is not only that it neatly serves the global right-wing narrative claiming that Trump “liberated” the Venezuelan people — and that we should therefore be not only grateful but even obliging to his objectives — but also that it further compromises our future. A society unable to add nuance or tolerate dissent across political extremes is one that cannot begin the work of reconciliation, let alone democracy.

We are losing sight of the fact that two things can be true at the same time: yes, Maduro was a dictator with ties to illegal economies and drug trafficking, and yes, Trump is violating international law by asserting unilateral control over the country.

Graffiti in the streets of Caracas of "Super Bigote," the superhero invented by Nicolas Maduro based on himself.

The world we inhabit, shaped by social media, pushes us deeper into sectarian ways of thinking and leaves little room for thoughtful analysis of political processes. We are constantly pressured to pick a side, because refusing to do so is often perceived as more threatening than choosing the wrong one.

This dynamic has profoundly shaped the way Venezuela is discussed. The Venezuelan narrative has become saturated with a worn-out refrain: “If you are not Venezuelan, don’t weigh in.” In practice, this is often a more palatable way of saying: we justify US intervention, and if you have not lived what we lived, you have no right to oppose it.

A man sits on a steep street in the La Vega neighborhood in Caracas, Venezuela.

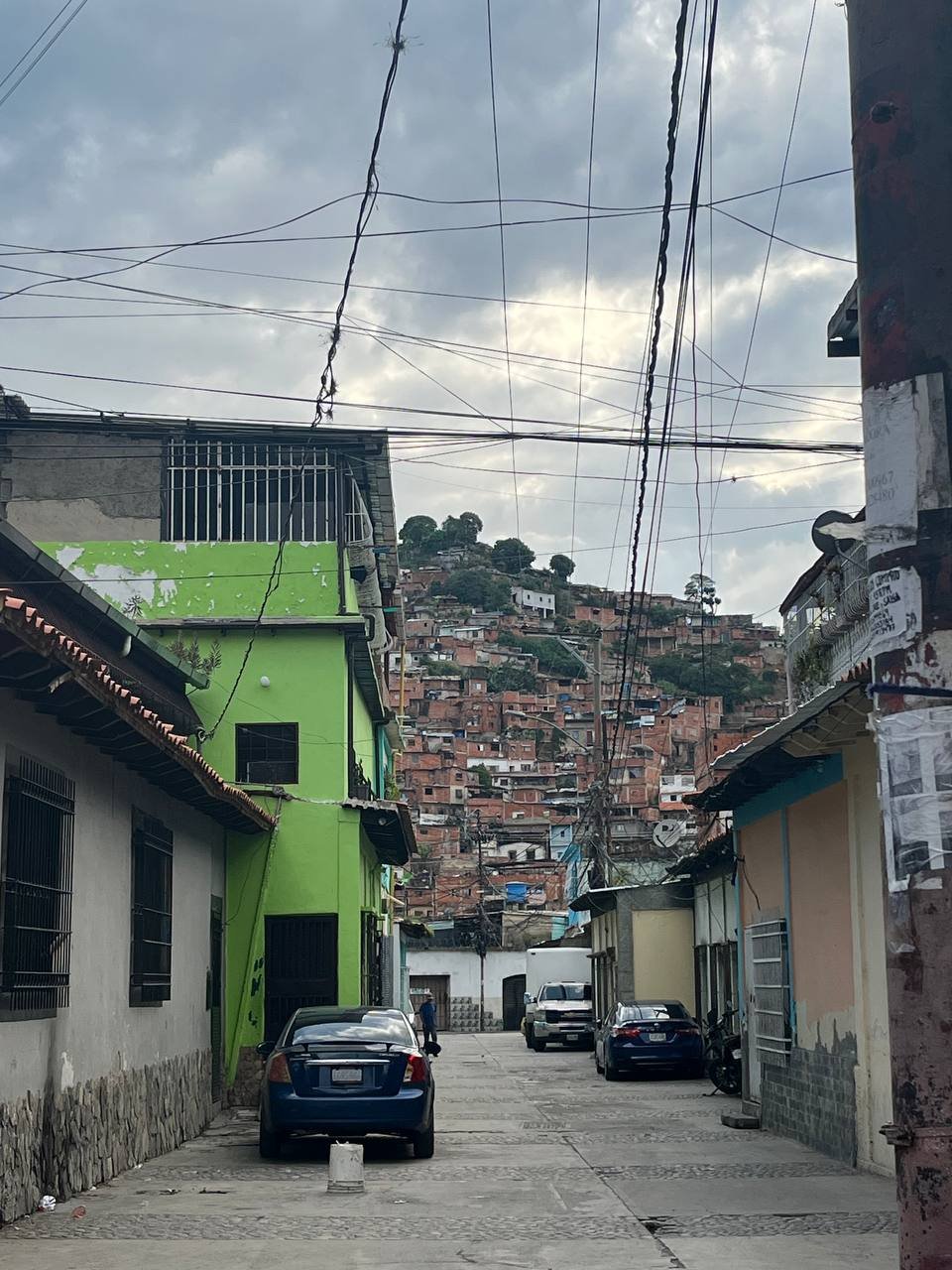

A woman looks back from inside a truck while climbing the steep streets of the working-class neighborhood of La Vega, where much of the population lives crowded along the mountainside.

When I visited Venezuela in October 2025 — traveling from Argentina, with Trump’s ships already in the Caribbean Sea while Maduro was still in Miraflores — a friend told me something I still repeat whenever I am asked for my opinion on the conflict: “It’s like being forced to choose between AIDS and cancer.”

Watching my home country being bombed, while having to repeatedly explain why I oppose it — and also explain that I am part of a diaspora that fled due to the atrocities of Maduro’s regime — has left me, and others who share my perspective, in a state of profound political alienation. That alienation is routinely pushed aside by the seductive clarity of arguments that demand absolute allegiance to one side or the other. In this polemic, I find myself caught on a razor-thin line where the only thing that seems to matter is being against the other.

The Venezuelan political self today has been stripped of its identity and reduced to a reflexive echo of Cold War–era arguments. In a society that shows little tolerance for disagreement or for occupying a middle ground, we have to ask: what kind of “democracy” can actually be built?

The low-income neighborhood of La Vega in Caracas, Venezuela.

Governments around the world — particularly in Latin America — have abandoned us. They proved powerless to confront Maduro’s regime even when its consequences reached their own borders through mass migration. Now, born of that same impotence, we are all left facing the raw force of American power, with as little agency as before. But we have also been abandoned intellectually. The idea of Latin America re-emerging as a global actor of consequence has been buried under Trump’s bombs, and those of us who still believe in the hemisphere’s political independence from the United States are dismissed as relics, or even as Soviet sympathizers.

As a Venezuelan living abroad who holds this position, I am not only worried about the future of the continent and the world it shapes. I also struggle to present myself within foreign societies, while enduring harsh criticism from my own compatriots, for defending a simple — yet deeply controversial — premise: real democracy and cooperation do not arrive through bombs falling from the sky.