What’s Left in Spain?

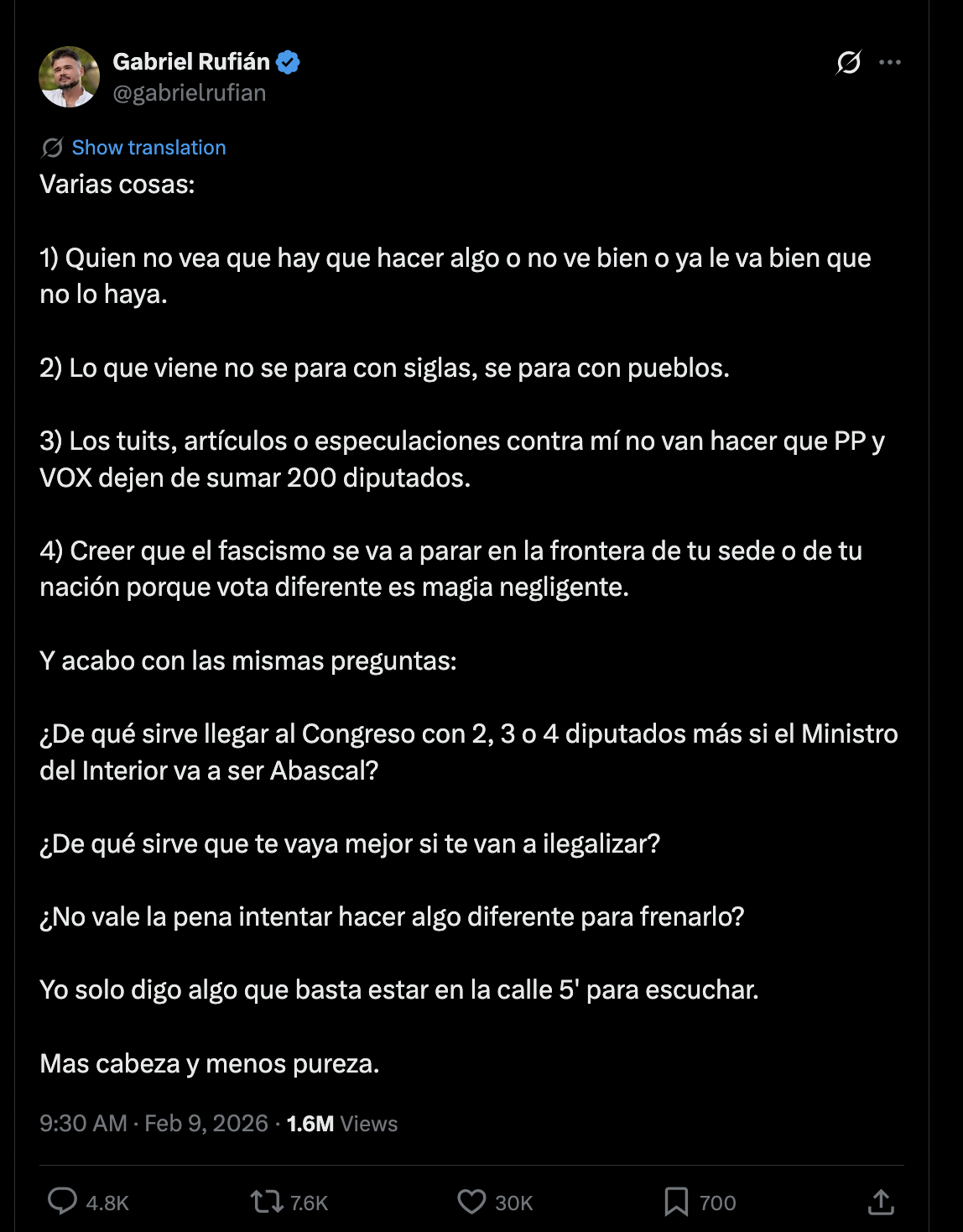

“Lo que viene no se para con siglas, se para con pueblos” (What’s coming can’t be stopped by acronyms - it’s stopped by the people”). With these words offered in a February 8 Tweet - a clear reference to the anti-fascist tradition and to the continuing rise of far-right power in Europe - Gabriel Rufián recently shook up Spain’s political scene by challenging the country’s many small, left-leaning parties, including his own, to check their political brands at the door and try overcoming their divisions.

Gabriel Rufián speaks in the Spanish parliament in February 2026.

From his platform as a member of parliament, a key leader of the Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC, the Republican Left of Catalonia), and an increasingly visible public figure with a million followers on X and more than 700,000 on Instagram, Rufián essentially accused his fellow leftists of living out the definition of insanity - doing the same thing over and over again while expecting a different result. His proposal has grabbed the headlines in a country where political news is normally dominated by the endless sniping between the two largest parties that take turns governing Spain: the conservative Partido Popular (PP) and the centre-left Socialist party (PSOE), which has led the ruling coalition since 2018.

Tweet has sparked intense discussion and debate about the present and future of the Left in Spain.

Given current realities in Europe and beyond, Rufián’s “gamble” (as it is widely being characterized here in Spain) came across as both a warning about the creeping MAGAfication of Europe and a call for the Left to play a decisive role in making sure Spain acts as a bulwark against this trend.

The specter of Vox

The immediate context for Rufián’s “gamble” concerns the growing electoral success of Vox, the far-right party led by Santiago Abascal. With its aggressively anti-immigrant, Islamophobic, and nationalist messaging, Vox has staked out a position to the right of the PP and has been employing a savvy social media strategy to make inroads among younger voters in particular. In addition, Vox performed well in recent regional elections held in the autonomous communities of Extremadura and Aragon.

Widely characterized by its opponents as a neo-fascist party, Vox also occupies a key position in the global, MAGA-inspired far right movement. Connections between Vox and MAGA architect Steve Bannon have been widely reported since the years of the first Trump administration, when Vox first entered the Spanish parliament. Since Trump returned to office in 2025, US officials have renewed their efforts to boost the fortunes of far-right parties throughout Europe. On February 11, the Guardian reported that senior US State Department official Sarah B Rogers has been “the public face of the Trump administration’s growing hostility to European liberal democracies,” with Rogers regularly taking to social media to attack European “policies on immigration and hate speech.”

Far-right politicians Santiago Abascal, Macarena Olona and Giorgio Meloni at an event in Marbella, Spain in 2022. (Image: Vox España, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

While Vox has never approached the level of electoral support needed to win elections on its own, it is taking advantage of an environment where neither of Spain’s two major parties can govern alone either. As negotiations continue over who will govern in Extremadura and Aragon, for example, it is widely assumed that the PP will need to turn to Vox in order to form a viable coalition. The PP’s leadership initially sought to maintain a rhetorical distance from that possibility, floating the possibility that it could govern with the help of abstention by the PSOE.

These machinations at the regional level have direct implications for the next national elections, currently planned for 2027.

In his recent remarks, Rufián has dismissed the PP’s efforts to keep Vox at arm’s length and warned Left parties against the temptation of going it alone. “What good is it to arrive in Congress with 2, 3 or 4 more deputies if the Minister of the Interior is going to be Abascal?” he asked, referencing the possibility of a PP-Vox coalition that could give Vox the power to wage a systematic assault on the Left. “What good is it if things go better for you if they're going to make you illegal? Isn't it worth trying something different to stop it?”

In this regard, Rufián’s warning appears to have been prescient. Spain’s public broadcaster RTVE reported on February 11 that for the first time, the PP leadership had acknowledged its willingness to partner with Vox in a hypothetical governing coalition at the national level.

A history of disunity

Meanwhile, Rufián’s efforts face considerable headwinds from within the Left itself. Infighting among Left movements and parties in Spain is legendary and dates back at least to the country’s civil war (1936-39), which ushered in the Franco dictatorship. While the PSOE played a central role in the early post-Franco period in building the country’s social democratic architecture, its subsequent shift toward a more neoliberal stance pulled the entire political system to the right and left many Spaniards feeling alienated. The famous indignados or 15-M movement that sprang to life in 2011 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis gave expression to this sense of hopelessness and anger at a political class beholden to elite interests.

Spaniards occupying the Puerto de Sol in central Madrid during the 2011 Indignados protests. (Photo: Jesus Solana from Madrid, Spain, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Out of this environment emerged Podemos, a new Left party that drew its energy from grassroots mobilization against neoliberal austerity measures. Much like Vox on the other end of the spectrum, Podemos shook up the complacent political class and forced it to consider new electoral calculations and coalitional possibilities.

At the same time, Podemos had difficulty building and sustaining meaningful alliances with other leftist parties as ideological and personal differences came to the fore. These dynamics were augmented by a sustained right-wing disinformation and “lawfare” campaign against the party. By the 2020s, Podemos was nearly or entirely absent from the formal political system, forced to concentrate its energy on earning representation in the European parliament.

Other key players on the Left include a number of regional and separatist parties (such as Bildu in the Basque Country and Rufián’s ERC in Catalonia) as well as the Sumar coalition, led by Yolanda Diaz, which has been part of the PSOE’s ruling coalition in recent years. Alliances among these various groups have typically been short-lived and often limited to running one-time slates for specific elections.

Rufián’s role

It is in this context that Rufián launched his appeal for what he called “mas cabeza y menos pureza” (“more brains and less purity”) from the Spanish Left. As the independent outlet El Salto put it, he has opted for “a tactic of controlling expectations,” resisting the urge to propose a specific coalitional formation or other concrete mechanism for creating formal linkages among leftist parties.

Instead, Rufián framed his message around the imperative of leaving aside old frameworks and grudges and thinking creatively about how to confront and defeat the far right. Meanwhile, he has maintained his role in parliament as a trenchant critic of the PP and its role in enabling the rise of Vox. On the issue of immigration, for example, he lambasted both right-wing parties for their hypocrisy in opposing the government’s decision to regularize the status of half a million immigrants in Spain while supporting “golden visas” and other fast-track options for immigrants who can afford to pay for them. “You all don’t hate migrants,” he pointedly said. “You hate poor migrants.”

Many observers have noted that Rufián is potentially well positioned to lead any political formation that might emerge from the current period of upheaval on the Left. While he has not foregrounded that possibility himself, his “adapt or die” message to his colleagues on the Left continues to reverberate.

What’s ahead and what’s at stake

The response from leftist parties to Rufián’s “gamble” was initially cautious. Bildu immediately issued a statement affirming that their priority is serving people in the Basque Country, while Rufián’s own ERC has essentially said the same with reference to its role in Catalonia. Podemos, once the standard bearer for an insurgent Left, now appears to be on an island with few, if any allies and no stated intention of contributing to a broader Left alliance.

As of this writing, however, there are also signs that space may be opening for a more substantial dialogue and for new strategic thinking on the Left. Sumar has announced its intention to work together with several other leftist parties in the next general election. Rufián described this as a positive step that he would be “foolish” to criticize, but emphasized that more work was needed in order to build a united front against the far right. Meanwhile, former Izquierda Unida (United Left) party leader Alberto Garzón, now a columnist for El Diario, celebrated these developments as “lights on the horizon for the Left” and an opportunity to confront the current “ecosocial crisis” and to push back decisively against authoritarian trends in the US and elsewhere.

On February 18, Rufián will appear in Madrid at a public event alongside Emilio Delgado of Más Madrid, one of the parties that has agreed to join Sumar’s new coalition, and moderator Sarah Santaolalla. This promises to be a key moment that may reveal whether Rufián’s call for “something different” has a chance of bearing fruit. Of course, a great deal could change between now and then as the Spanish Left continue to fight with itself over how to fight the Right.