What is the Greater Good?

Some activists can see past their own interests to advocate for “the greater good,” and some cannot. By accepting the feedback from community members, a broader, more inclusive perspective becomes possible, not only for the activist, but for the community as well. A recent news report from Buffalo, NY, is emblematic of the complexity of these dynamics. I offer the following commentary in the spirit in search of “the greater good” for all Buffalonians, but especially those who live in the Broadway-Fillmore neighborhood on the East Side.

The idea of “the greater good” is idiomatic, in that its cultural resonance differs from the literal meaning of the words. According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, “the greater good” refers to “help for most people in a society, especially when this involves harming one person or group or doing something that could be considered morally wrong.” Implicit in this definition are social justice and tough decisionmaking. When alluding to “the greater good,” a choice is typically made to help a majority of people even at the risk of hurting a critical minority.

In this commentary, I claim that residents protesting alleged criminality in their Broadway-Fillmore neighborhood actually define “the greater good” for their minority group, not for the majority of residents in the neighborhood. I also suggest one way to address the problem so that it does improve the experiences of a majority of people in the neighborhood.

Public health crisis at the Polish Veterans Park

In a July 10, 2025 Channel 7 ABC WKBW Buffalo news story by reporter Kristin Mirand, Buffalo City Council Member Mitch Nowakowski called on the Buffalo Police Department’s Behavioral Health Captain Sharese Saleh and Erie County Health Commissioner Dr. Gale Burstein to provide data on the increase in the number of incidents of substance abuse and mental health crises in the Fillmore District which he represents. Nowakowski told the reporter, “[W]hat I'm looking forward to is how Erie County Health Department and BPD and local agencies can come together to tackle this issue once and for all."

Buffalo City Council Member Mitch Nowakowski.

Council Member Nowakowski was responding, in part, to a critical mass of community members voicing their concerns about unhoused people residing in a local park. Chief among the local activists was Lisa Lewandowski-Stoll, who joined with her neighbors in 2024 to restore the Polish Veterans Park. “It was all community members,” she recalled, “all race, creed, color, everybody coming together and enjoying the park.” A little over a year later, however, the park had become a makeshift home for unhoused Buffalonians, some of whom were using drugs. “[As of] four days ago,” Lewandowski-Stoll said in the WKBW report, “[the park] was overrun…It became an encampment where drug activity is happening.” Fueling Lewandowski-Stoll’s distress was the transformation of the park from a site for community get-togethers and recreation activities to a “tent city” where drug paraphernalia was among the refuse where homeless people were sleeping at night.

July 10, 2025 video report by Channel 7 ABC WKBW Buffalo news reporter Kristin Mirand

A contradiction in terms

As a catalyst for change, Lewandowski-Stoll was doing the right thing - i.e., calling on the local news to bring attention to the emerging public health problems in her neighborhood like homelessness, prostitution, and substance abuse. Unfortunately, she was less concerned for the individuals struggling to keep roofs over their heads than the threat to her specific community’s quality of life. This community implicitly excluded the people facing homelessness, drug addiction, and mental health crises. “While I feel saddened for the people that are suffering with addiction and the prostitution, and the activities that are going on,” Lewandowski-Stoll explained, “my overall interest is in the greater community and the greater community good.”

As a community leader, Lewandowski-Stoll presumes that the “greater community” includes people like herself, unafflicted by addiction, prostitution, and mental health crises. This is her call for “the greater good,” because not all people will benefit from her activism.

What gives me pause is the shortsightedness of her strategy. Clearing out and cleaning the park by her house does little to remediate the problem facing the unhoused people and even less to improve the greater Broadway-Fillmore neighborhood. In fact, I maintain that she’s advocating for a minority perspective and approach to community uplift and claiming it will help a majority of people. Rarely, if ever, has increasing the criminalization of unhoused people in an historically impoverished neighborhood equaled “the greater good.” Rather than advocate for universal housing and universal health care, for instance, Lewankowski-Stoll called on law enforcement to remove the unhoused people so her family and friends can play at her neighborhood park.

Affordable housing is the greater good

Alarmingly, the cornerstone issue of housing found little attention in the Channel 7 news report. Instead, the report connects the homelessness of the people resting in public spaces of the neighborhood exclusively to drug use, criminal behavior such as prostitution, and mental health disorders. The fact that the park’s inhabitants have no shelter is given no substantive treatment. This glaring silence permits the implication that homelessness is a failure of character not a failure of city infrastructure or an indictment of the larger social system. This is where we need more “honest discussion” if we are to clear out parks, as Buffalo’s political and community leaders are requesting.

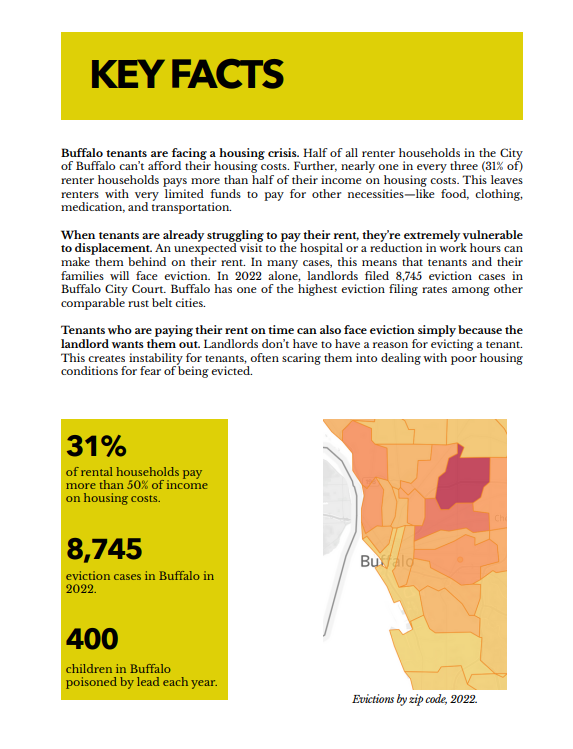

In Buffalo, there’s a housing crisis. According to community think tank Partnership for the Public Good (PPG), more than 30 percent of Buffalonians who rent apartments pay more than half of their income on their housing bills. The pressure that housing costs and rapacious landlords put on renters led to more than 8700 eviction cases in 2022, a figure that continues to grow to this day. So pervasive is the housing crisis that PPG and their community partner Western New York Homeless Alliance warns that “the number of unhoused residents in Buffalo more than doubled between counts in 2022 and 2023.”

Fact sheet on Buffalo’s housing crisis published by the Partnership for Public Good (PPG).

In the summertime, the effects of Buffalo’s housing crisis are on display, as unhoused people leave the shelters and abandoned buildings where they hide all winter in order to rest outside where there’s fresh air and more space. Buffalonians sometimes can ignore how big the problem has become because most of us are motorists and conveniently drive by destitute people and places all the same. I’m a pedestrian, though, so I see the crisis in slow motion, and sometimes the crisis gets close enough to touch me…

Do we have an unhoused population involved in substance abuse and criminal activities? Yes, we do. Are these elements related - i.e., using drugs, committing crimes, and living unhoused? Yes, they are. But if we want to solve other big problems like substance abuse and open-air criminal markets, I contend that we must call on the city, county, and state to address the housing crisis so that all people have access to safe, affordable housing.

A return to failed approaches

Besides, other approaches to solve these problems are ongoing, and so far they are ineffective. Buffalo, for example, has had a zero-tolerance police policy since 2006. So-called “broken windows” policing is so hegemonic that residents use the local news to report on unhoused people as if they are the broken windows to which local law enforcers must respond. The local news report referenced above is a case in point.

The reality is that the failure of Buffalo to address structural issues like housing hurts way more people than the Buffalo police can arrest and the Erie County Holding Center can detain. There’s more than 10 years of data showing this policy doesn’t actually fix the problem.

What our elected officials and community leaders have not done is create a citywide universal housing campaign to ensure that all Buffalonians have shelter. Much more common are private interests looking out for “the greater good” of Buffalo by hoarding landholdings and marketing them at exorbitantly high prices to wealthy buyers from more expensive housing markets outside of Buffalo. This is how Zillow ends up calling Buffalo a “hot market” for housing. It’s also how out-of-town developers relocate here to build structures that no one in Buffalo can afford, as they seek to profit from what they have perceived to be cheap land. All of these factors make it more likely that the unhoused population in Buffalo will grow in the coming decade.

Getting to the roots

I’m proud of my city, because Buffalo is full of everyday leaders who care about their communities and who call on journalists, policymakers, and law enforcement to make improvements that benefit the greater good. All I ask, right now at least, is that we reimagine what “the greater good” is so that our social and political strategies can address root causes of public health problems like the chronic lack of dignified and affordable housing.