No Price Tag for the Priceless

On July 14, 2025, a caravan of more than a dozen residents of the Upper Peninsula (UP), Michigan, drove as far as nine hours to meet with lawmakers at the Capitol in Lansing and urge them to deny a grant of 50 million taxpayer dollars to fund a proposed copper sulfide mine.

Participants gathered in front of the Michigan Capitol Building in Lansing. (Photo: Steven Holt)

We sleep on sofas, we sleep on floors. We snarf down bagels whilst memorizing talking points. We do a quick round of roleplay with our partners, then fling ourselves into a labyrinth of government offices and battle our nerves to meet with legislators.

That same afternoon we drive back home, six to nine hours. I am among those traveling the farthest, and past midnight am still hurtling through the rain pelting down in the biggest storm of the season. I collapse into bed and dream I’m running late to a meeting but trapped in an elevator to nowhere. A week later, I am still recovering.

“There is local, well-reasoned opposition”

Can you imagine making such a trip to fight a subsidy to a mine? When was the last time you thought about mining? I mean this not as a critique, because until just recently, mining for me was just another phenomenon belonging to that invisible dimension of “Things You Don’t Think About Despite Them Being the Foundation to Your Reality.”

Normally, mines are like factory farms: tucked away in remote, uninhabited regions, far from the highway, with no big flashing arrows pointing out their existence. This particular mining proposal is no different, except that in this case, the remote, uninhabited region is often full of humans: Porcupine Mountains State Park contains mainland Michigan’s largest unlogged, old growth wilderness area. It has been ranked as the state’s favorite park, and even as the most beautiful State Park in the country. Over half a million people come here each year in search of peace and quiet in Nature, of a clear view of the starry sky, of fresh air and birdsong, and of that eerie thrill of knowing that bears, wolves, and cougars might be watching from the shadows.

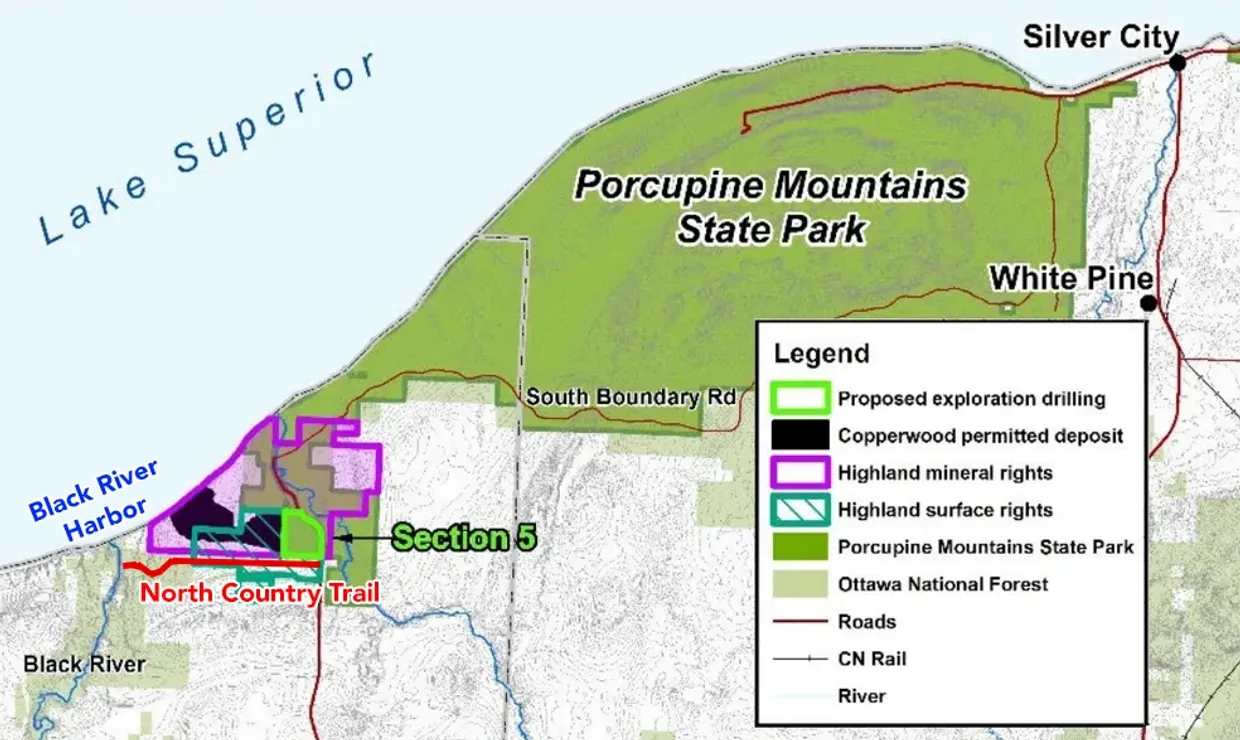

But the proposed Copperwood Mine would share a border on two sides with the Park. Not only that, it would seek to mine underneath Park property. Beyond the extraction, mining requires non-stop lighting, rock grinding, conveyance systems, exhaust ventilation towers, sewage lagoons, power generation, heavy industrial traffic, cell towers, subterranean blasting, and more.

Map showing proximity of proposed Copperwood Mine to the Porcupine Mountains, Lake Superior, and North Country Trail, with a mineral deposit overlapping with the State Park’s Presque Isle Scenic Area.

For Steve Holt, one of the caravan’s participants from Gogebic County where the mine would be located, such industrial activity is entirely antithetical to the spirit of this place.

“I want legislators to see there is local, well-reasoned opposition,” Steve said before the trip. “I want them to understand the lasting damage to our wilderness-loving tourist economy from feeling blasting, 24-hour lighting in what should be a Dark Sky Preserve, and constant rumbling from 10 years of mine operations, followed by the permanent visual scar of a gigantic pile of toxic tailings visible from every ski hill in the area and a perpetual source of dangerous contamination into Lake Superior when the acid and heavy metals pollution breaks free gradually, or potentially catastrophically. The economic boom and bust of a mine will bring social problems and will not serve our communities well.”

Some elaboration is required regarding Steve’s reference to “a gigantic pile of toxic tailings visible from every ski hill,” because “copper mine” does not tell the full story — in fact, it tells only 1.45% of it. The deposit in question is copper sulfide, meaning that copper itself is just a small fraction of the ore, so for every ton mined at Copperwood, only 30 pounds would be copper and 1,970 would be waste, requiring on-site storage. Why must that waste be stored? Because it’s toxic: compounds like mercury, arsenic, cadmium and lead exist in concentrations underground which do not exist on the surface, and when they’re wrenched up, pulverized and mixed with water to free the copper nuggets through flotation, the resulting sludge has to go somewhere.

The copper rush

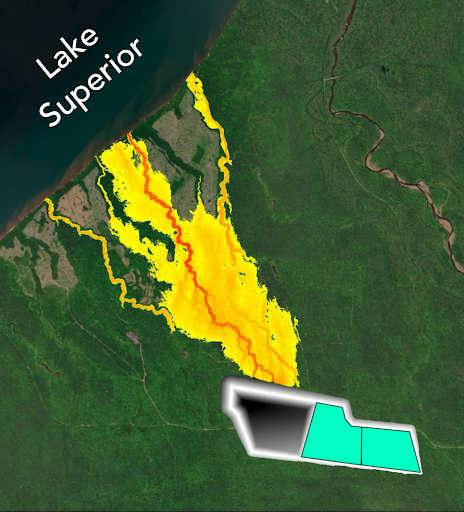

In Copperwood’s case, over 30 million tons of the stuff would be stored in a “tailings basin” (a mine waste pond) over 244 football fields in area, on downward-sloping topography, in the closest such waste facility to Lake Superior on record. A model by the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission shows that a dam rupture would send that waste many meters deep surging into the lake in as fast as 21 minutes.

Copperwood dam rupture model. (Image: Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission)

But “we need copper,” so the State of Michigan is considering sacrificing the iconic wilderness character of one of its most beloved areas and storing 278 Capitol Buildings’ worth of toxic waste next to the continent’s largest freshwater reserve, all for the sake of this shiny metal with semi-conductive properties.

The importance of copper has been touted in recent years due to its role in emergent “artificial intelligence” infrastructure, alternative energy production, or simply for the sake of “national security stockpiling.” The exact narrative is ever shifting in the political winds, but at least for the industry, the takeaway is always the same: we want that copper, and we want it now.

But we’ve come to make the case that other resources must also be considered.

At the time you’re reading this, the price of copper is most likely somewhere between $4.50 and $6.50 per pound. But in an era when over 95 percent of the original forest in the United States has been cut, what is the price of healthy old growth? And when the population is increasing exponentially as the Earth grows hotter and drier, what is the price of the largest, cleanest, and wildest of all Great Lakes?

Mining companies, the businessfolk who support them, the lobbyists, the accountants, and the politicians who determine the fate of so much money: none have an infinity button on their calculators. Consequently, they almost always fail to take account of resources with value beyond reckoning.

That’s why we’ve come to the Capitol: to rip the price tag off the priceless.

Porcupine Mountains State Park as fall colors begin to change. (Image: Sol Anzorena)

A tale of two heritages

In a land where many streets, parks, and newspapers are named after mining (my local rag is called “The Pick & Axe”), and where grey mining murals adorn many a downtown, the slogan “mining is our heritage” is not uncommon to hear. And it’s true: for those descended from European settlers, the 19th and 20th centuries in the Upper Peninsula were largely defined by extraction. Of course, the story often fails to mention the mining revolts, the deaths and disease, the substance abuse, the disappeared Native women and sex workers, the environmental devastation lasting far longer than the mine itself, and the small fact that almost all of the wealth produced was exported to financial centers hundreds of miles away, leaving behind a void in the economy from which much of the UP is still struggling to extricate itself…

Still, heritage is heritage.

But for Charlotte Loonsfoot of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, the mining ventures of the past two centuries are but the blink of an eye. True heritage goes back far deeper.

“This cause is important to me because Lake Superior was the home of my ancestors, just as it’s my home today,” Loonsfoot says. “None of us who live here can afford any more pollution than is already in the Lake from past mining.”

Charlotte is one of today’s advocates at the Capitol, and she also joined us in last September’s Gichigaming Water Walk, when members of seven Tribal Nations along with non-Native allies carried water 31 miles on foot out of concern for the proposed mine.

Charlotte Loonsfoot at the Gichigaming Water Walk, September 14, 2025. Her skirt reads: “No Pipelines, No Mines.” (Image: Charlotte Loonsfoot)

The Native People of the Lake Superior region are called the Anishinaabe, also known as the Ojibwe and Chippewa. According to some accounts, the Anishinaabe migrated in from the eastern Great Lakes, while others suggest they were actually returning to their prior origins. I shall make no attempt to speak on their view of their own history, but I can say with certainty that Native People were here when Lake Superior was born, some 12,000 years ago. And at around two billion years of age, the Porcupine Mountains are among the oldest mountains in the world. So to define mining as heritage is to mistake the foam for the entire sea.

Fortunately, more and more in the UP, us newcomers are coming to agree with those whose roots go deepest: this region’s real heritage is its vast waters and spectacular Nature.

A moment of contention

In general, lawmakers and their staff are friendly and receptive to our common sense argument: we aren’t asking you to oppose mining, nor even to oppose this mine necessarily, but since copper is not even a critical mineral — meaning no risk of undersupply — then why accelerate Copperwood’s development with taxpayer dollars? Is it really fair to ask Michigan residents to fund such a disruptive operation at the worst spot imaginable?

“The trip to the Capitol was a resounding success,” said Madison Carico, one of the participants from Marquette, the UP’s largest city. “The careful considerations of everyone we spoke to truly left me feeling hopeful that Lake Superior will remain clean and safe from any further contaminations for years to come with the refusal to use taxpayer money to fund the Copperwood mine, a costly project for the state, both economically and environmentally.”

Participants gathered for a training session on how to speak with lawmakers. (Image: Steven Holt)

Many officials tell us with certainty that they will not support the funding. Others are not yet ready to take a firm stance, but it’s clear their thinking on the matter is evolving in our direction. But there’s one office where we might as well be banging our heads on a two-ton chunk of native copper.

Representative Greg Markkanen represents the district where the proposed mine would be located. After our campaign mobilized tens of thousands to see a grant of $50 million to the mining company stall first in July 2024 and then again in December, Mr. Markkanen introduced a new $50 million grant request on April 23, 2025, as a sort of backup plan should the previous grant fail for a third time. He made a few interesting alterations: whereas the original grant mentions “Copperwood” or “the mine” no fewer than 34 times, Markkanen’s grant mentions it a grand total of zero times, and instead names the local township as the recipient.

Some might call this a sneaky tactic, since the mining company’s newest press release confirms that, whether or not the mine is actually named in the text, both grants are seen as equivalent in their purpose of rolling out the power grid, cell towers, and industrial roads necessary to enable Copperwood’s development. Additionally, from his previous statements, we know that the company’s CEO would tout approval of either grant as a “true endorsement” from the State of Michigan.

Members of the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa reveal banner outside of the Capitol in Lansing, Michigan. (Image: Tori Solis)

The heavy task of visiting Markkanen’s office is charged to Tori Solis of the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, the closest Michigan Tribe to the proposed mine site. For Tori, as for Charlotte and many other Tribal members, denying taxpayer funding to this project is a matter of respecting the text of the 1842 Treaty, which guarantees Tribes the right to hunt, fish, and gather from the land and waters as they have since time immemorial — a right which means little unless the ecosystem remains clean enough to healthfully sustain her community.

“When I mentioned that this project would violate 1842 Treaty Rights, Markkanen’s staff member Beau LeFave said this was a huge accusation,” Tori said. “Interestingly enough, our pregnant women are currently only allowed to eat one fish from Lake Superior because of the environmental impacts of previous mining projects in the area. When I asked why the representative hasn’t engaged in government-to-government relations with our Tribe, Mr. LeFave stated it was the Tribe’s responsibility to invite the Representative to the table in order for them to have their voices heard. In my opinion, Representative Markkanen does not deem Tribal Nations nor our Treaty Rights to be of utmost importance. It’s more crucial now than ever that Tribal Nations and Indigenous-led Organizations join in solidarity and defense.”

Tori’s final sentence is in reference to a sign-on letter she authored in opposition to the state funding. Her Tribe is seeking solidarity both near and far in their fight, so the reader is encouraged to join us in circulating this letter to relevant contacts.

Tori and Charlotte outside Mr. Markkanen’s office giving two thumbs down to the sticker, “Support U.P. Mining.” (Image: Steven Holt)

My deeply contrarian nature leads me to visit Markkanen’s office shortly after Tori’s group. For me, it’s a little more personal. His chief staffer LeFave called me “Mr. KansasCityCarpetBagger” in a recent email and dismissed my perspective simply because I was not born and bred here. On one hand, they complain about declining population; on the other, they don’t take kindly to folks moving in and having opinions. Well, now that he’s heard from a few Tribal members whose people were rowing the Lake in birch bark canoes way back when his great-great-grand-spermatazoa was still flopping around in France, I’m wondering if Mr. LeFave’s views on the “insider-outsider” dynamic might have changed?

In short, they have not. But I am grateful to hear his perspective, which (paraphrasing) is that his community has participated in mining for generations, and so now to hear so many people challenging a mine is, to his ears, an offense against that legacy.

I could tell LeFave that it’s alright for some traditions to change (see: bullfighting, slavery, and many others), but I would be committing the same error as Copperwood’s supporters. They speak in generalities; they employ vague narratives related to “green energy,” or “national security stockpiling,” or AI, depending on what’s politically en vogue; they cite jobs numbers and projections of tons to be mined; they speak as though the project exists purely on a computer screen and entirely fail to mention the real physical location where it would be sited. For evidence, just see this opinion piece authored by Markkanen and other UP lawmakers, calling Copperwood “the answer to America’s copper shortage.” Despite the fact that the highest authority on the matter has deemed that there is no copper shortage, the article commits a grave lie of omission by neglecting to even utilize the terms “Lake Superior,” “Porcupine Mountains,” or “North Country Trail,” which would be Copperwood’s immediate neighbors.

Copperwood would be the closest metallic sulfide mine to Lake Superior on record. (Image: Sol Anzorena)

That’s all I want to communicate to Mr. LeFave: a mine does not exist in a vacuum. We are not here to challenge all mines, nor even this one. We are only asking to leave taxpayers out of the equation and let the free market take it from here.

But alas, before my head splits on that two-ton copper boulder, I decide to take my leave. I say, “I won’t ask for a hug, but how about a handshake?” His colleague, who until now has been avoiding all eye contact, finally unleashes a shriek of laughter, as Mr. LeFave reaches an arm my way.

Out of sight, but not out of mind

“It was important for me to meet with lawmakers in person and show that residents of the UP aren’t a monolith,” said Carly Rusch, a cultural resource management professional from Gogebic County. “We care deeply about the environment and the wellbeing of everyone who lives in and around the Great Lakes. That means protecting our water from pollution in the face of short term economic gains. The UP needs better long term plans for economic improvement that doesn’t put our natural resources and citizens at risk from pollution due to ill advised mining ventures.”

The caravan to Lansing was organized by Jane Fitkin from Citizens for a Safe and Clean Lake Superior, in collaboration with myself from Protect the Porkies, along with others. We are extremely grateful to everyone who made this trip possible, such as our host Alexandra, who somehow emptied out three whole houses to accommodate us.

At the end of that long, hot and hectic day, I consume enough watermelon to feed a hog, then commence the long drive home. On the way, Jane and I have a conversation about distance.

Jane says that most people these days have very little idea where their food comes from. Relatively few have gotten their hands dirty to harvest a potato; fewer still have beheaded a chicken. “But what about everything else?” she asks.

What about the steel in this car we’re driving? The glass of the windows? The plastic, the synthetic fabrics, and all the materials we’ve never even thought to name? What of the copper and other minerals in this device upon which I’m currently writing, and in the one through which you’re reading? We receive these items fully-formed, as if by magic, with no evidence that they are but the final stage of a long chain of steps, including distribution, transport, manufacturing, smelting and processing, mining, and all the tremendous habitat destruction required to turn Nature into a blank slate before construction even begins.

Correction: these technologies are not the final stage, because when they stop working, either due to planned or unplanned obsolescence, they go back to whence they came, out-of-sight and out-of-mind, and then it’s the Earth’s problem — that is, until we recognize that what affects the Nature affects us, since we are Nature.

The Porcupine Mountains contain the largest remaining old growth eastern hemlock population in the United States. (Image: Sol Anzorena)

If the key to revolutionizing our food system is to eliminate distance by re-immersing ourselves in community gardens and volunteering at local farms, then what is the key to revolutionizing material culture more broadly? What would the world look like if there really were big flashing neon arrows telling us where all the mines are? What if we each had to chop the forest, excavate the wetlands, and reroute the streams ourselves, as part of a standard high school education? What if, in addition to taking a body count at conflicts in Iraq, Ukraine, and Gaza, someone started counting all the deaths required to make a smart phone?

I know such a world will not come into being any time soon. But it might at least enter into our thoughts. It also does not escape my recognition that, by the twisted humor of the universe, we’ve employed many of those very same technologies created through anonymous distance — the car, the computer, and others — as tools with the purpose of eliminating distance in our trip to Lansing to fight sacrificing more Nature in the name of said technology.

To block the Michigan grant twice last year required mobilizing tens of thousands to eliminate distance by writing emails on glowing crystals with rare earth mineral bellies. Through multitudinous microchips and much electromagnetic wizardry, our voices reached further than the loudest megaphone could ever take them. And now, to make those voices even more clear, we’d just transported ourselves in ginormous hunks of steel in order to transcend our existence as a name on a screen or spreadsheet statistic and become real living, breathing, flesh-and-blood humans in front of our lawmakers.

Thanks to all those magic minerals and a fair amount of fossil fuel, Mr. KansasCityCarpetBagger finally got to shake Beau LeFave’s hand!

The Presque Isle River at Porcupine Mountains State Park, adjacent to the proposed Copperwood mine site. (Image: Sol Anzorena)

The irony of it all must not escape us, but may that irony serve as a seed for something greater. Our campaign encourages everyone, all over the world, to begin developing awareness of how all this stuff comes into being, and to begin questioning to what degree that stuff is useful and happiness-inducing, or simply a self-perpetuating quasi-lifeform whose reproduction has gone unchecked, like horny rabbits without an apex predator, which, though prone to dying quickly, decays far more slowly than old-fashioned carbon-based life and risks leaving us shivering in the shade of a monumental waste pile to the moon.

Curiosity is the cure. Look into how your food is made, how your stuff is made, how your laws are made. A YouTube video is a start, but nothing beats eyes on the ground.

Not mine: ours!

The word “Mine!” is what the toddler yells when he doesn’t want to share his toys. It is the very cornerstone (pun intended) of our egocentric civilization. Thus, our best hope for a better world lies in analyzing our relationship with extraction. One day, perhaps the toddler of Progress will stop screaming “Mine!” and learn to say, “Ours.”

That means thinking about not just about what is profitable for a few select individuals, but what benefits the collective, of which we humans are but a small part. To the degree that we will continue mining copper and other metals, we must weigh each mineral’s utility against higher-priority interests: those of the community, of the First Peoples, and of Life Itself.

Participants from Lower Michigan, Marquette, and the Lac Vieux Desert Tribe. (Image: Alexandra Leonard)

Was our trip to the Capitol enough to convince lawmakers that we’re all in this together, and that it would be most politically savvy to save taxpayer funding for projects which don’t inspire a petition of nearly half a million signatures in opposition?

Celebrated water warrior Charlotte Loonsfoot has left in good spirits. “I trust in our legislators to make the best decision for our Water’s future,” she says, “because soon it's going to be far more valuable than any minerals.”

_______________

To learn more, visit www.protecttheporkies.com and www.citizensforsuperior.org.