Always Already Anti-Fascist: Lessons From a Lifelong Spanish Militant

As a committed Weave News grassroots journalist for nearly 20 years, I have always been inspired by Woody Guthrie’s famous observation that “all you can write is what you see.” Woody spent his life engaging in his own kind of people’s journalism, taking what he saw and channeling it into melody and verse. He has also been in the news recently, with a newly-released set of home recordings drawing new attention to “Deportee,” his legendary song about the anonymous deaths of migrant farmworkers. Could any song be more timely in 2025?

What you see, of course, depends on who you are, where you’re located, and what you’re looking at. I recently moved from the United States to Spain, so I am looking back at the US from a place that has its own turbulent history. Spain’s past century has been marked by struggles over and against a fascist project that remains undeniably present, even in a supposedly “democratic” age.

As a new arrival, I feel like I am simultaneously “here” and “there,” but also neither here nor there. I’m still trying to figure out what it means to be positioned in this particular way at such a terrifying moment in our collective history. The vectors of fascist brutality that tore families and communities apart during Spain’s civil war (1936-39) and the global horrors that followed now seem to be bent on bulldozing almost every democratic institution in the US. They are also aiding and abetting genocide in Palestine, accelerating the climate crisis, and spearheading a vicious backlash against those who have been fleeing their homes in the face of relentless capitalist extraction and apocalyptic violence.

The wisdom of experience

In the face of these intolerable realities, I am opting for a kind of grassroots journalism that tries to look in multiple directions - in this case, toward the US from Spain and vice-versa - and to create dialogue across borders and experiences. This kind of journalism can operate like a hinge: connected but also connecting, enabled by being grounded but also (hopefully) enabling something larger to be built, solidified, maintained, and expanded.

This week I found inspiration and insight in the story of Cristina Farré, a lifelong antifascist militant (more on this word below) whose autobiography, Ho Vam Donar Tot (We Gave It Our All), was recently published in Spain. In an interview with Sandra Vicente published by the Spanish independent outlet El Diario, Farré spoke about her incredible and often painful history of activism, imprisonment, exile, and return, as well as the ongoing urgency of antifascist struggle.

Author and activist Cristina Farré. (Photo: Albert Salamé/Vilaweb)

Farré, whose political action has been animated by revolutionary communist, anti-imperialist, and feminist commitments, described the process of writing the book as deeply fraught but ultimately worth it: “it’s a very profound exercise that makes you relive many things.” By having the courage to share those memories in writing, she has offered wisdom that has tremendous value in our own moment of antifascist reckoning.

Throwing Franco out the window

Stories of university students occupying administration buildings form part of the lore of student radicalism throughout the world, with the wave of student uprisings in the late 1960s often serving as a prime example. Farré recalls the incident that directly led to her own period of living in hiding and, eventually, in exile. On January 17, 1969, Farré and her classmates made a fateful decision:

Until then, the University had been a sacred place, like places of worship, and the police didn't enter. But that day they entered, and it was because the rector had authorized it. We held a very tense meeting and decided to go to the rector's office to throw him out. There were more than 150 of us at the beginning, but by the time we got to the door, there were only 10 of us left. Everyone had chickened out. Even the rector chickened out and left. We snuck into the office and were amazed by the carpets, the red curtains, and the gilded frames. Suddenly, on a pedestal, we saw a bust of Franco. Don't ask me whose idea it was, but the fact is, we opened the windows and it flew out.

Tossing out a bust of dictator Francisco Franco was a tremendously symbolic and dangerous act in a country where Franco’s hold on power had been near-absolute since the late 1930s. Already a committed activist at 19 years old, Farré needed to abandon her studies and go underground in order to stay ahead of the police.

LEFT: Bust of the Dictator Francisco Franco (1938), by the sculptor Francisco Asorey González. Military Historical Museum of A Coruña (Galicia, Spain). (Photo: Fernando Losada Rodríguez, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons). RIGHT: A 3D-printed bust of Donald Trump currently selling for $75 on Etsy.

About a year and a half later, however, she was arrested and thrown into the notorious prison in Alcala de Henares, just outside Madrid. And just like that, she had become a political prisoner.

The commitment of militancy

In Spain, the word “militant” (militante) has a corresponding verb, militar, that is commonly used when describing an individual’s commitment to join and be active in a political party or other political organization. While the word “militate” exists in English, it is rarely used in this sort of context. For example, one would never say, “I spent my life militating for the Democratic Party.” A word like “activism” has become so overused and watered down (and often subject to derisive critique, whether from anti-”woke” voices on the Right or from those on the Left with a more radical or revolutionary orientation) in the era of social media that it can’t possibly convey the depth of commitment that militar does in Spanish.

Militants from the Mujeres Pan y Rosas movement at a 2022 International Women’s Day march in Spain. (Photo: Artistosteles, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Farré was born into a militant family. Her father had been sent into exile under penalty of death for belonging to the anti-fascist camp during the Civil War. She was most famously affiliated with the Partido Comunista de España (Internacional), a small Leninist/Maoist party that used “urban guerrilla” tactics as tools for fighting fascism, building working-class power, and supporting the liberation of oppressed peoples in Spain and throughout the world.

The Partido Comunista de España (Internacional) used as its flag a version of the Catalan Estelada.

The party, which emerged through a series of schisms with other communist groups, was only around (and perpetually banned) for a few years during Spain’s transition from dictatorship to democracy. Like many on the Left, she insists that La Transicion was a myth used to convince Spaniards that working-class resistance was no longer needed.

In the interview with El Diario, Farré speaks of her anti-capitalist, anti-fascist, and feminist militancy in the context of her time as a political prisoner, when she was subjected to torture. “It’s painful to remember,” she acknowledges, “but at the same time it makes me proud of myself. They tried to break me by torturing me, but I managed to maintain my dignity.” In doing so, she says, she stayed true to her fundamental commitments as a militant:

When you decide you don't like this world and want to change it, militancy and life become one and the same. I'm a mother and I'm a militant. I study and I'm a militant. So, when I'm a mother, I'm also a militant. When I study, I’m also a militant. And when I'm in prison, I'm also a militant. I focused on the regular prisoners, whom I consider victims of capitalism, and on victims of gender violence. I tried to improve their living conditions as much as possible. The struggles one can wage in prison are limited, but in that year and a half, I did what I could.

Exile on the edge

After her release from prison, Farré refused to comply with the government’s order to check in with the local police in Barcelona once a week. Instead, she chose to go underground once again, living clandestinely for a decade, during which she started raising two children who had to live with the knowledge that their mother could be arrested at any time. Eventually, her family made the decision to flee the country altogether. But where to go?

As she recalls, “any European country was out of the question because of extradition.” So the first stop was Algeria, where she worked as a journalist. Her partner had participated in the country’s struggle for liberation from French colonial rule, a struggle that had made Algeria, in her words, “like the Mecca of revolutionaries around the world.” Soon, however, Farré and her family found themselves caught in an emerging civil war in which some factions saw all foreigners, regardless of their ideology or level of integration, as the enemy.

“We had to leave no matter what, but we couldn't return [to Spain] because, even though the statute of limitations was almost up, I still had pending charges,” she remembers. “We started asking around, and a friend at the Colombian embassy told us they respected refugee status there, so that’s where we went.” Unfortunately, they arrived as Colombia was in the midst of a horrifying period of political violence fueled by the rise of drug cartels and the impact of US imperialism.

After two years, they decided to go to another Mecca for revolutionaries: Cuba. And once again, the shadow of imperialism loomed large:

I knew the history; I'd never been there before, but it was as if I'd lived there. But of course, at that time, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the brutal US embargo, the situation was extremely difficult. Instead of saying they were having blackouts, they had occasional ‘lightning strikes.’ It was hard and disappointing, but really, how were they going to maintain the socialist project? They were on their own in an embargoed country, an island in the middle of an underdeveloped region. We couldn't have expected anything other than what ended up happening.

Refugees, disowned by democracy

Had she been born a decade or two earlier, Farré might have found herself in Algeria or Cuba during the heady days when these countries played central roles in a global network of anticolonial radicalism. Instead, she witnessed the impact of the counter-revolutionary forces that the anticolonial writer Frantz Fanon warned about, combined with the impact of the disastrous “War on Drugs” and the omnipresent Western “divide and rule” strategies.

Exiled members of the Black Panther Party in Algiers. (Photo: Justin Giffords, “Eldridge Cleaver’s Algeria”)

The year 1975, often regarded as the symbolic end of the “long 1960s,” was also the year when Franco died, opening a space for Spain to create a new constitution and eventually hold multi-party elections. Yet for Farré, her own situation as an exiled radical gave the lie to the rhetoric of democracy. While in Algeria, her family had managed to get approved for refugee status, but the Spanish government refused to provide them with the documents necessary to return home. “We're a very strange case because, although there were refugees from the Civil War, we were among the very few from the Transition,” she observes. “And that put us in a tough situation since Spain didn't recognize us because, you know, democratic Spain didn't generate refugees.”

In short, she and her family found themselves in a Kafkaesque situation of “democratic” statelessness:

The thing is, we wanted to leave again, but our lawyer warned us that we had become stateless. They could kick us out of the country and even make us disappear, because we didn't exist. It was very dangerous, so we flooded the newspapers with letters. And through this pressure, we managed to get them to give us our papers.

Their persistence finally enabled them to return to Spain in 1996.

Legacies of struggle

One of the most distinctive elements of the past century in Spain is that the country contains the traces - sometimes extremely visible, sometimes less so - of a tremendous range of parties, organizations, and movements that have participated in the struggle against fascism. Their ideological orientations range from democratic socialism to militant anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism to various forms of revolutionary communism, feminism, and mainstream trade unionism.

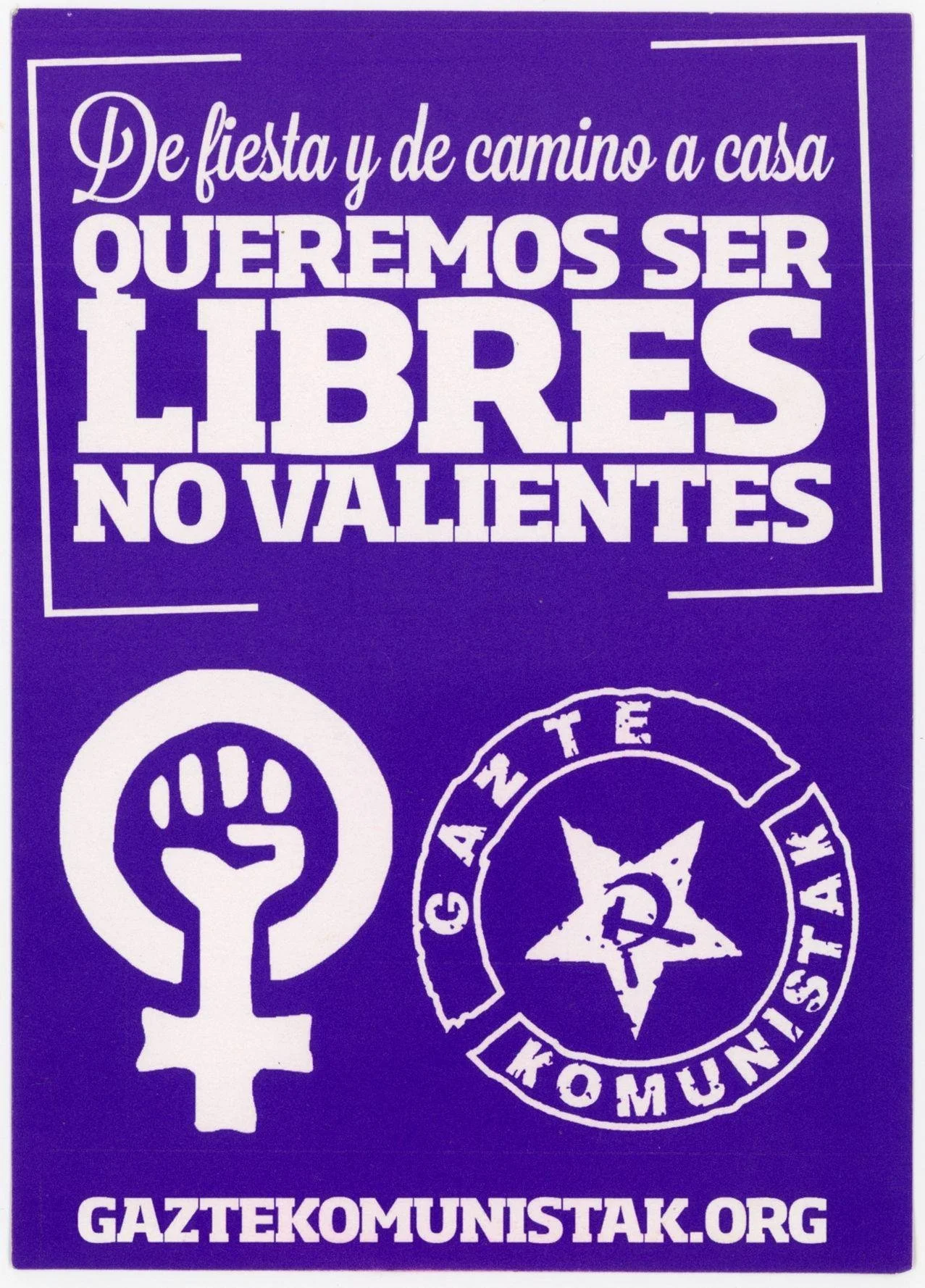

Spanish political stickers courtesy of St. Lawrence University’s Street Art Graphics digital archive.

The history of infighting among these groups is undoubtedly real, but Farré insists that we must also remember the history of common struggle. “When I was young,” she says, “do you know how many of us were giving it our all? Many, and from many parties that might have had differences, but we were all there.”

Farré also offers a clear-eyed recognition of the other side of the coin:

The repression didn't end with the end of the dictatorship. Dissent is still not accepted today. There is no democracy or anything like it here, and there won't be as long as there is torture and political prisoners continue to be imprisoned. It's a constant trend since the Civil War. But we will continue working and fighting, organizing ourselves, until the spark ignites and we return to the barricades. Because that will happen, inevitably. When? Well, when we're fed up with enduring this situation of injustice. It will cost us a lot, a lot, but there is no other way, because what we are experiencing now is extremely brutal. To a certain extent, it may be more difficult for us now than before…

One of the most essential lessons of this history is that for all the talk of revolutionary purity and discipline within specific organizations, there is great value in building coalitions that rely on a diversity of tactics. Even more fundamentally, Farré’s long, transnational saga reminds us that the fight against fascism is not confined to specific moments or locations; rather, it is an ongoing commitment that responds to an ongoing reality. In this sense, whether anti-fascism can “win” is beside the point; what matters is that the struggle must continue.

Excerpt from the lyrics to Woody Guthrie’s song, “Little Seeds.” (Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc.)

When asked whether her lifetime of militancy, with all of its associated personal costs, was “worth it,” Farré doesn’t miss a beat, offering a ringing endorsement of the sort of anti-fascism that Woody Guthrie would surely recognize:

Without a doubt. It's one of the things I'm most certain of in life: it was worth it, and it continues to be worth it. We have to try and give it our all. I think we left a legacy, a school of struggle, and the promise that future generations will be able to look back without feeling ashamed that we didn't fight. We stood up for many just causes and defended them to the very end. And that seed will grow. Definitely.