The Battle for Quinta Torre Arias: From Common Ground to Private Playground

Once a noble countryside estate, Quinta Torre Arias is now a public park in the Spanish capital, Madrid, with gardens that welcome the community. However, current Madrid mayor, José Luiz Martínez-Almeida of the People’s Party, has different plans for the park, and the threat of its return to privatization looms.

Perks of the Park

Located not far from my study abroad homestay in Madrid, Quinta Torre Arias was the perfectly motivating place in which to run. Its contrast between light stone doric columns, a black, delicately patterned iron archway, and sculpted acorns that rest above the columns on a platform illustrated the grandiosity and elegance through which its architects hoped to demonstrate the power of the elites. Walking (or running, as I would) into an alley of exquisitely manicured dwarf pine trees, entering an oasis. Hidden away from the bustle of the busy road, I experienced relief from the rush of Madrid’s urban life.

Entrance to Quinta Torre Arias. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

Shortly after the alley, a red brick building with black wooden balconies and curved Edetania roof tile was once presumably used as the soldier’s post that guarded the entrance to the estate. If this building was where I was stationed, I suppose I wouldn't mind being that guard.

Assumed gate soldiers post. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

Turning right, one enters the community feel of the park. Here, gardens bursting with color are run by the municipality, featuring the smells of sweet flowers. Edible plants such as strawberries, oregano, rosemary, and mint are planted for people to freely pick, smell, and help cultivate. But the once grassy pathways are now dusty and dry. As I mentioned in my first Weaving the Streets article, Spain is experiencing a significant drought resulting from climate change, and Quinta Torre Arias illustrates that neither community parks nor noble estates are spared by the global catastrophe.

Gardens of Quinta Torre Arias. (Photos courtesy of the author.)

Strawberry box. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

From left to right: lavender, mint, oregano, and rosemary. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

A little further up the path, a composter encourages people to recycle their biodegradable materials in hopes of propagating more plants, using an approach that “significantly cuts down on the amount of trash in a landfill and reduces the costs and carbon emissions reducing waste in landfills.” This small but mighty community garden is a way for people to take pride in their surroundings, interact with neighbors, and grow fresh food for themselves. These public benefits will be lost if the park is forced to become privatized under Mayor José Luiz Martínez-Almeida’s plans.

Composter of Quinta Torre Arias. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

Leaving the gardens, a slight hill leads to the palace of Quinta Torre Arias. The red bricks, large windows, turrets, black iron balcony, and large tower with a clock in the center of it capture my attention and signal that this was once home to nobility. The palace itself is under restoration, so I could not access the interior, but the exterior spoke to the luxury that I expected within. Gazing upon the palace, I imagined the countess of the day strutting the halls and bathing in the sun striking through the large windows.

Front side of Quinta Torre Arias. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

Towers of Quinta Torre Arias. (Photos courtesy of the author.)

Walking towards the unusually dry field (as a result of climate change and growing temperatures globally) in front of the palace, two wooden sculptures of a Siren and a train were constructed using dry wood that the gardeners and planters collected. These wooden sculptures engage passersby and allow for community members to showcase their wood carving skills and passion. As a community space, Quinta Torre Arias has a little bit of everything for all.

Wooden sculpture of a Siren. Title and Artist unknown. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

Wooden sculpture of a train. Title and Artist unknown. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

History of Quinta Torre Arias

Quinta Torre Arias was home to many members of Spanish nobility dating back to 1600, most recently Countess Tatiana Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno in the 20th and 21st centuries. The countryside home or “quinta” consists of a chapel, stables, gardens, several other buildings including a greenhouse, and the main palace, Palacio Quinta Torre Arias. In 1986 with her husband Marquess Julio Peláez Avendaño, the countess signed an agreement with the City of Madrid that the estate would become property of the city but remain in usufruct. That is, the city would use and derive benefit from the property, but it would remain in the countess’s name. After her death in 2012, the property became municipal, and in November 2016, its doors reopened to the community. Quinta Torre Arias is now a “Cultural Interest Site” of the Community of Madrid.

People Power Through Posters

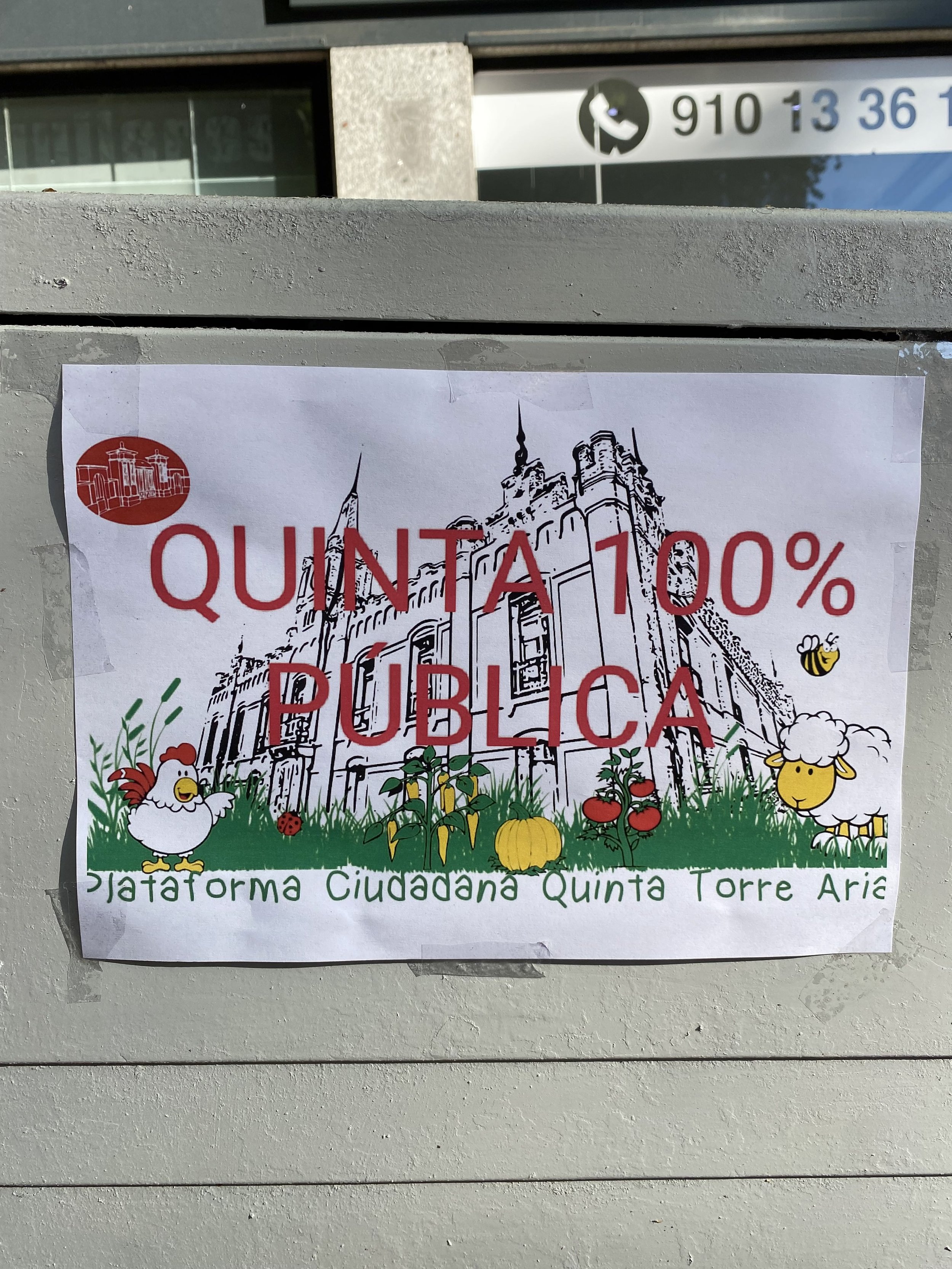

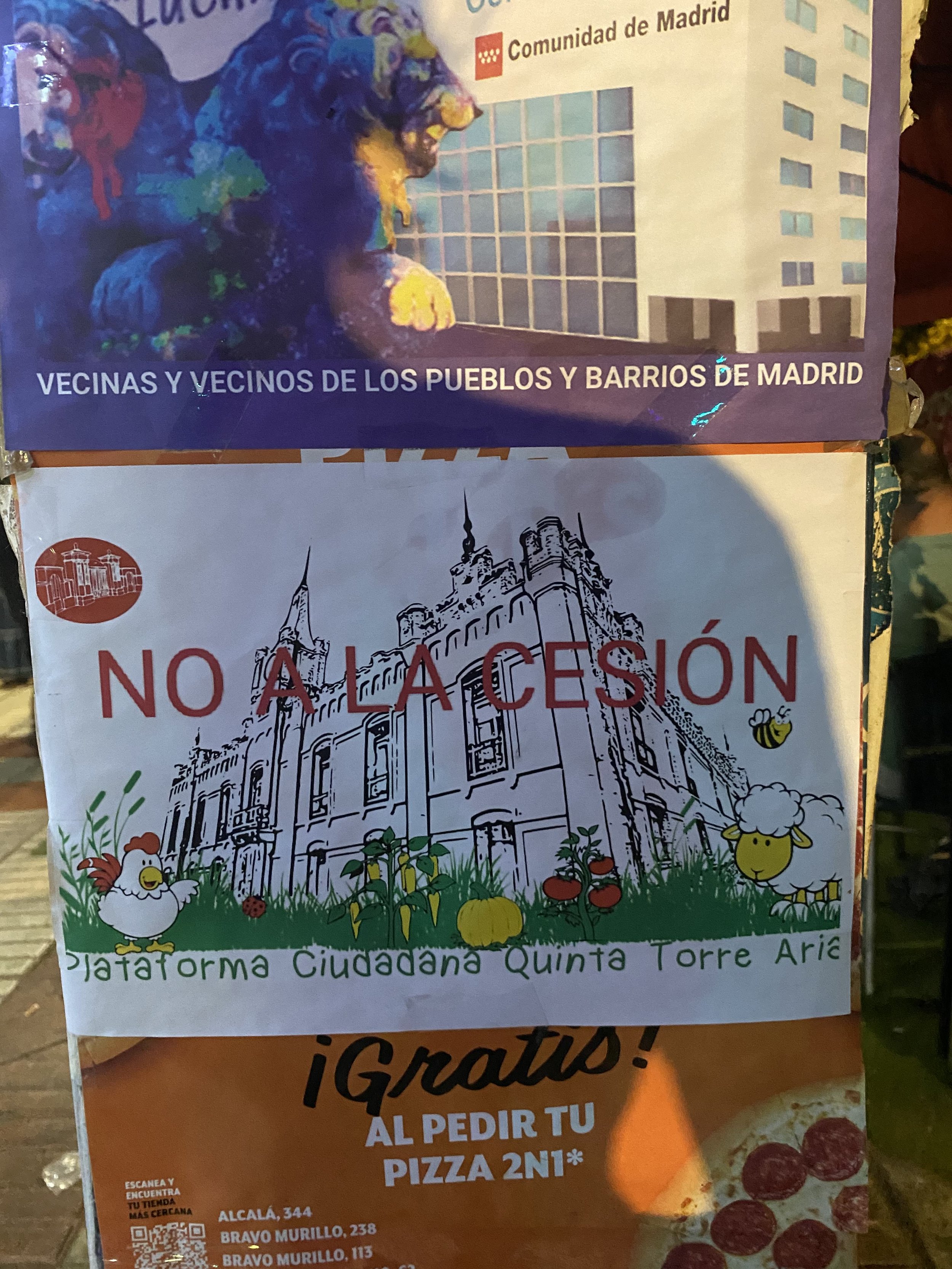

My metro stop entrance near where I lived was right outside of Segunda Humana, Ciudad Lineal. I used this stop daily and it served me well. Coming out of the metro stop one day, two posters on an electrical box located near Segunda Humana caught my eye. Surrounded by other posters offering to buy gold or silver, promoting public healthcare, and advertising a pizza shop, the first read “Quinta 100% Publica,” or “Quinta 100% Public,” and “No A La Cesión,” or “No To The Cession.” Both posters include an outline of the palace in the background, with a chicken, sheep, ladybug, bee, fruits, and vegetables displayed in the foreground. Both are signed by the Citizen Platform of Quinta Torre Arias. Having found the Quinta Torre Arias open when I visited it previously, I was confused by the message. Seeking to understand this call to action, I did some research.

“Quinta 100% Public” and “No to the Cession” posters by the Citizens Platform Quinta Torre Arias. (Photos courtesy of the author.)

I discovered that Madrid mayor José Luiz Martínez-Almeida (an already unpopular mayor) has aspirations to privatize the park, citing that the current management of the park (led by the municipality and the community) is ineffective and inefficient. Almeida hopes privatization would generate revenue that could then be distributed back into other parks and spaces in the city. He has stated that the current management of the park is public (one of the only ones in the city) has resulted in uncleanliness and lack of security. With a professional management team, he aspires to improve the quality of the park and better aid the community.

What Almeida fails to understand is that the people care for this park and are willing to work for it. They are willing to dedicate themselves to improve this green space and create a community haven in a historically palatial environment. As illustrated by these posters, local residents are furious with this possible outcome and believe that this historic park needs to be municipally run.