“We are More”: Public Art With a Purpose

When I knew I was going to live in New York City during an off-campus study program in the fall of 2022, one of the things that excited me the most was all of the art I would be exposed to in such a major urban center with people from all around the world. I am not talking about the famous artwork you would find in the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Museum of Modern Art, but rather the public art you see walking the streets of the city. I am talking about the word “Peak” written with a marker in most of the subway stations on the green line. I am talking about the worn-down political stickers pasted on trash cans and stop signs. I’m talking about the colorful and vibrant murals made by world-known artists such as Keith Haring and Bansky that are free for anyone to see. I am talking about street art.

Discovering the politics of street art

My interest in street art started in Mexico when I learned about ‘Los 3 Grandes’ in middle school. ‘Los Tres Grandes’ [The Big 3] refers to the three most important muralists in the country: Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco. I remember learning about them in class as a child and being mesmerized by their ability to translate their ideologies and beliefs into art. At that time, as a 13-year-old, I was very early on my journey to discover my own ideologies and beliefs, but their art fascinated me.

Ever since that day, I have paid attention to all the art that surrounded me, starting with my hometown of Tijuana and the ever-changing art on the Mexican side of the wall. In my adult life, my interest in street art translated to my travels, where I started paying attention to the different types of public art and started questioning the presence and absence of street art in different places.

Now, as an international student and a Mexican immigrant in the US, I have begun to recognize that street art has always been political. Throughout this series, I will feature three street artists’ public artwork in NYC and explore the purpose behind making their work public.

Art within and beyond the museum

For my first Weaving the Streets installment, I will begin with Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, an artist I learned about during my first week in the city. Ironically, I first discovered her public artwork in the Museum of the City of New York. I am glad museums are featuring more art that tries to send a message and call to action and art that goes beyond beauty and aesthetics. The museum had an immersive installation by Phingbodhipakkiya titled “Raise your Voice,” which combined a selection of works from her public art campaign “We are More” with the original artwork of activists and allies such as Yuri Kochiyama and Malcolm X.

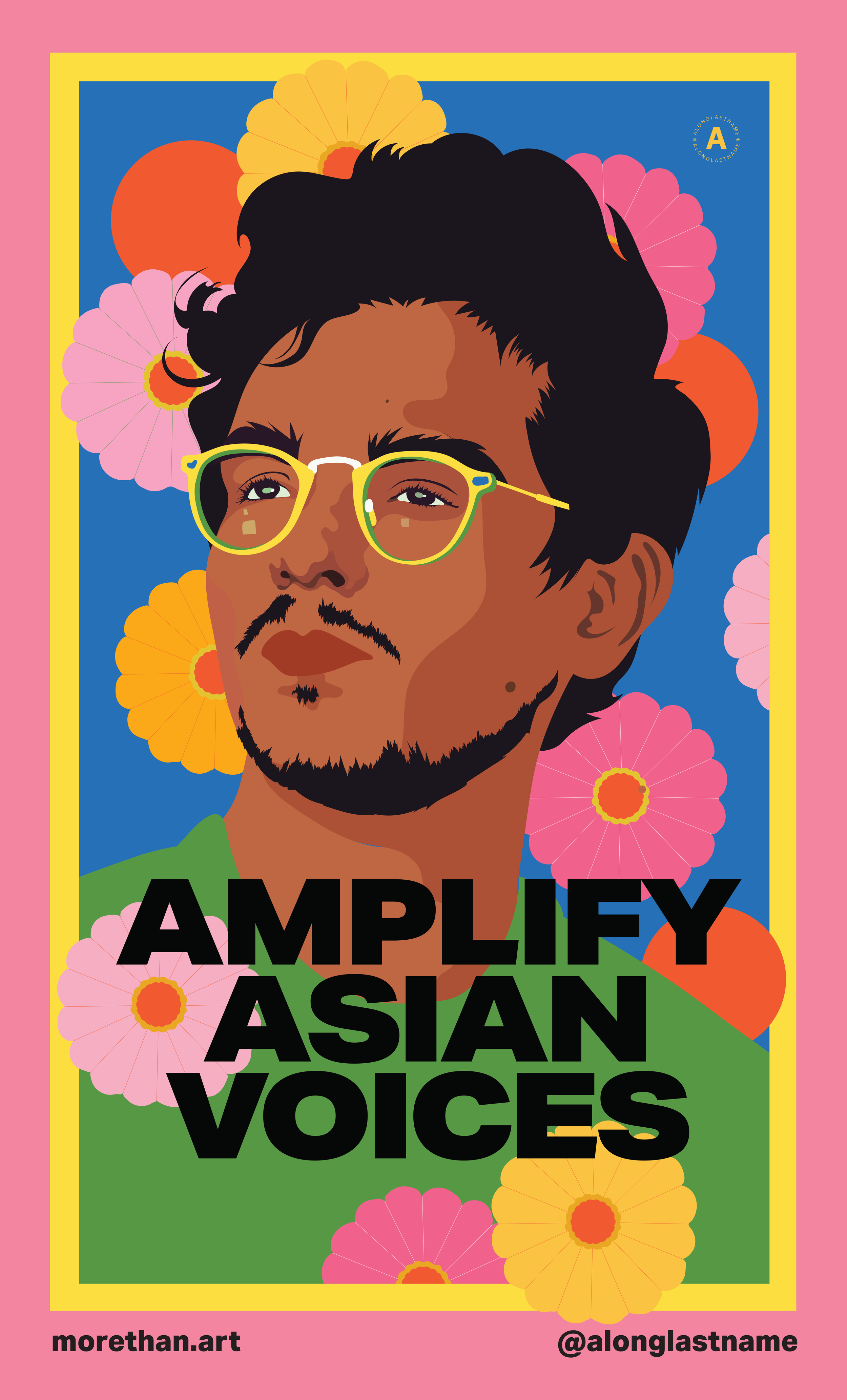

When I first saw the mural at the beginning of the exhibition, I was immediately drawn towards its vibrant colors. In this installation, Phingbodhipakkiya asks questions such as “Where do you belong?” and “How will you resist?”. There was an iPad with her public artworks, and that is where I saw some images from her “We are More” campaign, and I felt very connected to her work.

A couple of weeks later, I was walking through Times Square when I recognized the same vibrant colors and strong statements. I was lucky to have found the last couple of posters remaining from her public art campaign, “We are More.”

Phingbodhipakkiya’s art encourages you to stop and reflect. The public nature of her eye-catching work encouraged me, and likely thousands of others walking down the crowded NYC streets, to consider individual and collective attitudes towards specific societal groups. It calls out double standards when it comes to appropriating a culture instead of appreciating it.

When I see her art, I feel relieved and understood. I feel like someone has put into words and images what I don’t know how to say about my own culture, but it also makes me reflect on how I perceive cultures that are different from mine.

Art for everyone

Like Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, most street artists' philosophy and their preference for public art are related to accessibility. In an interview with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, she spoke to this idea:

If it is a large canvas inside a gallery, somebody outside of the gallery might not see it. But if it’s on the side of a building, anybody passing by will see it. You don’t have to pay an entrance fee, or you don’t have to be someone who’s particularly “cultured” to experience or enjoy public art.

In addition to its reach, many artists use it as an opportunity to reflect on specific topics. Phingbodhipakkiya’s mural work, for example, deals with themes like reclaiming space for unspoken narratives and amplifying the visions of people and ideas that she believes should have more of an audience. She uses her public art campaigns as a medium to speak about the collective experiences and struggles of marginalized communities. She uses intense colors and simple language to catch people’s attention. Viewers quickly understand the questions she raises, and her work creates space for them to reflect on their own place in it.

Responding to bigotry

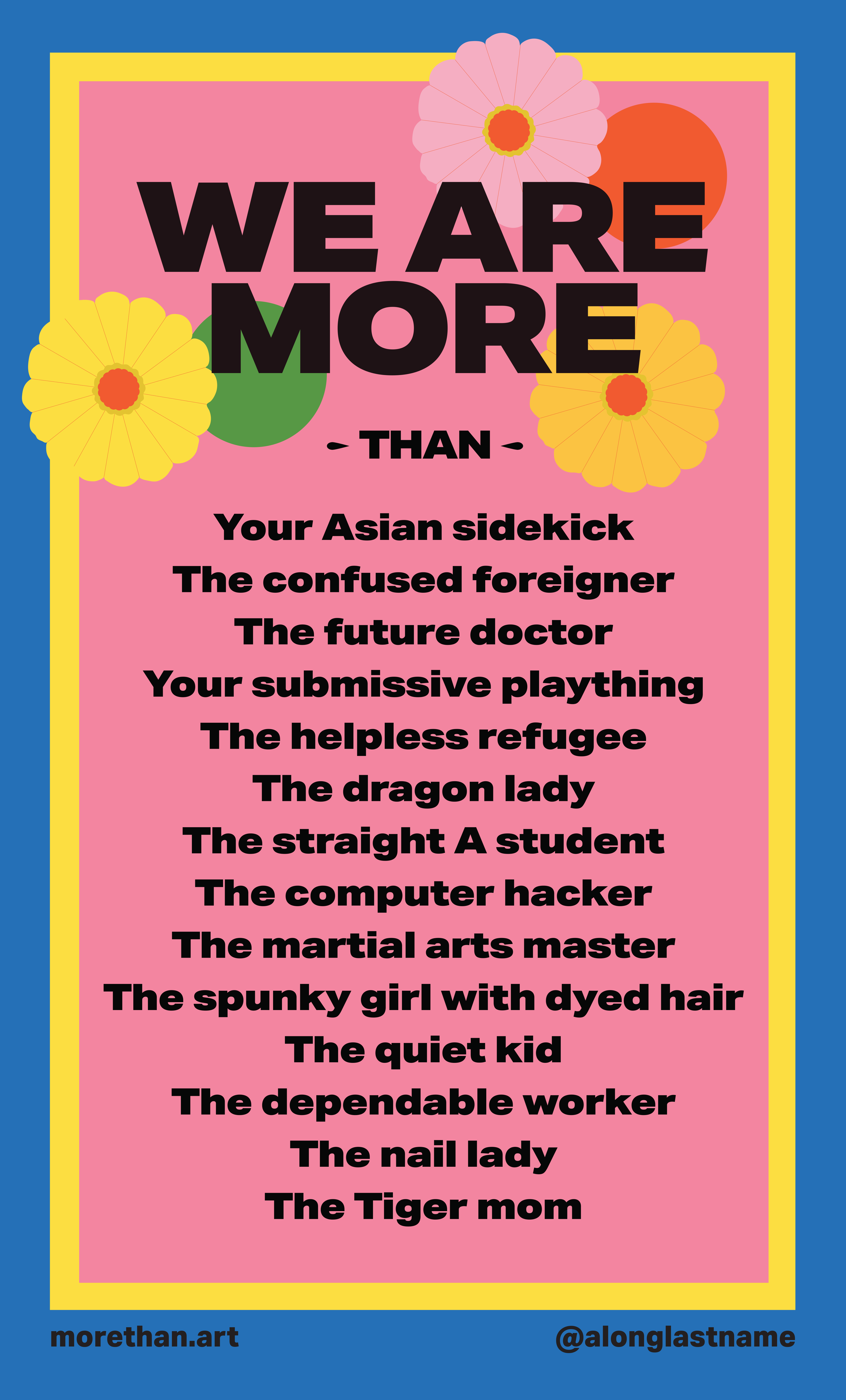

“We are More,” the exhibition I saw in the Museum of New York and on the streets of Times Square, began during the pandemic in response to the massive wave of anti-Asian bigotry that surfaced amidst stereotypes and misinformation about the origins of COVID-19. Phingbodhipakkiya makes it very clear in her art that this hate did not just begin with the pandemic. She invites the population to reflect on years of discrimination against Asians in the United States.

In her campaign, Phingbodhipakkiya raises very powerful questions such as: “When will you be welcome, not just included?” and “When will others love us as much as they love our food?” Even though her campaign revolved around her personal identity as a Southeast Asian woman, I related to it as a Mexican migrant to the US. I have experienced a similar alienation of my culture and personhood, but my culture and I are one and the same. For me, Mexico is more than celebrating Cinco de Mayo and famous beaches catering to tourists; it is where I grew up, it is my family, and it is my safe place.

A chance to reflect

I invite you, the reader, to look at street art and murals - the same way Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya wants you to - as an opportunity to reflect. Even though her “We are More” installation is mostly gone now, it is still available to view online. What I love the most about street art is that it often has a message in contrast to museum art. That is why it is put in such a public place to begin with; it is up to us to discover the artist’s meaning or to give it meaning ourselves.

In Phingbodhipakkiya’s case, her art invites us to reflect on the collective experience of marginalized communities. This raises thousands of questions: Why is marginalization a collective experience? Why do people from countries thousands of miles apart have the same experience in Western countries like the United States? What does this tell us about Western countries? In my next article, I will interview a street artist born and raised in New York City regarding his vision of public art and the city’s street artist community.

All images provided by the author.