Ecuadorian Paro Nacional: The Power of Grassroots Mobilization

Between Monday, June 13 and Thursday, June 30, Ecuador experienced an 18-day paro nacional (national strike) led by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), who were protesting against the regressive and austere economic policies of the current right-wing president, Guillermo Lasso.

This was certainly not the first national strike in Ecuador, nor was it the first time that Ecuadorians have protested against the neoliberal economic policies that have historically disenfranchised the country’s Indigenous and impoverished communities. The willingness to shut down Ecuadorian society as an act of protest, despite the subsequent harsh economic repercussions of such mass mobilization, illuminates the fervent desperation of the Indigenous communities and other social groups within Ecuador as well as people’s desire for drastic political, social, and economic change.

The core demands

CONAIE had a list of 10 demands (see also this summary in English) including

the reduction and freezing of fuel prices

more time to pay off bank loans/ protection from banking and financial sectors

fair prices for agricultural products

price controls for essential products

a ban on mining projects in Indigenous lands

effective policies to end drug trafficking and violence

increased funding for healthcare and public education

employment opportunities and labor rights

an end to privatization of public companies

respect for the 21 collective rights of Indigenous nationalities of Ecuador.

Throughout the 18 days of the strike, the country was almost entirely shut down. Roads and highways were blocked, and stores were mostly closed or only discreetly open. The road closures in particular caused major food and gas shortages throughout the country. By the second week, grocery store shelves in Latacunga, where I am currently living, were nearly empty. Once the paro entered its third week, many homes (including the apartment building where I live) no longer had gas to cook nor to heat the water in their homes.

During these 18 days, most civilians moved around by foot, bicycle or motorcycle because protestors would often slash car tires in order to promote solidarity in advocating for their demands. Numerous other social organizations took to the streets, including the National Union of Educators, the United Front of Workers (FUT), and the National Federation of University Students of Ecuador, to name a few. The university where I work in Latacunga was entirely shut down during the first two weeks of the paro due to student and staff involvement in demonstrations.

Tires and burnt sticks blocking the Panamerican Highway south of Quito (Photo: Julio Estrella / EL COMERCIO).

Photo from the rooftop of my apartment building in Latacunga. You can see that all storefronts had their grates completely shut, or only discreetly and partially opened. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

Essential context behind the strike

In October 2019, under former left-wing president Lenin Moreno, CONAIE led another national strike to protest against an International Monetary Fund (IMF) decree that had been implemented in March 2019. This decree required certain structural adjustment measures involving the reduction or elimination of fuel subsidies, tax cuts for large companies such as extractive oil and mining firms, as well as the revocation of certain worker’s rights to make the labor market more flexible. The resulting increases in the cost of fuel and overall cost of living prompted the ten-day national strike, which ultimately led to the withdrawal of the IMF decree and the reinstatement of the subsidies.

Despite the protest’s success, Moreno implemented additional austerity policies such as cutting funding for health care, which severely hindered Ecuador’s ability to effectively provide resources for and combat the COVID-19 pandemic. As in numerous countries around the globe, especially in the Global South, the pandemic had deleterious impacts on Indigenous and low income communities that are still being felt today.

Prior to the pandemic, Ecuador was already facing complex economic and social challenges. In December 2019, 25 percent of the population was already living in poverty, and by mid-2021, this figure had grown to 32.2 percent. Despite the economic damage caused by the pandemic, Moreno continued to prioritize capital over human interests by further imposing neoliberal policies.

For example, in May 2020, Moreno once again removed fuel subsidies and adopted a system in which fuel prices fluctuate monthly based on the price of oil, a decision that inevitably led to further price increases. President Lasso, who succeeded Moreno in May 2021, has only upheld and further implemented neoliberal policies, including the increase of fuel prices and privatization of state companies.

The power of the “blank vote”

Now you may be asking yourself, how did a right-wing candidate who would only augment harmful neoliberal policies win this election following the backlash against Moreno’s austerity policies? I had the exact same question, so I did some digging.

I learned that Yaku Peréz, who represented the left-wing Indigenous Pachakutik party, also ran in the 2021 presidential election. However after losing in the first round of elections, Perez claimed election fraud. As an act of protest against this alleged fraud and more generally against establishment politics, Perez subsequently called on his supporters to cast a null, or blank vote in the second round of elections, inadvertently creating the conditions for Lasso’s electoral victory.

This election proved devastating for left-wing and progressive parties, as it was overtly transparent that Lasso, a natural representative of the business sector, would further open the country to foreign investment and thus prioritize privatization, natural resource extraction, mining, and the easing of labor restrictions. The null vote has been viewed as having “symbolic weight”, serving as a premonition for future political conflict led by the Indigenous movement. Such conflict has been prevalent throughout nearly the entire first year of Lasso’s presidency and certainly appears to have reached its pinnacle during this most recent national strike.

Resisting austerity

In August 2021, just three months into Lasso’s presidency, protesters took to the streets to speak out against his continued implementation of neoliberal policies. In September, Lasso reinstated the IMF agreement inherited from the Moreno administration to help revive the economy. This decision only further cut social spending and continued to protect corporate interests rather than those of the middle and working classes. Leonidas Iza, the leader of CONAIE, recently expressed in an interview that the IMF policies have only worsened the economic effects of the pandemic on impoverished communities.

Furthermore, on October 22, 2021, Lasso repealed the May 2020 decree that increased fuel prices on a monthly basis, effectively creating fixed fuel prices that far exceeded prices in the world market. This continued implementation of austerity policies engendered further protests in September and October 2021. In addition to opposing the price increases, protesters were also advocating for more funding for education, as well as policies that would guarantee fair prices for produce and require the government to purchase produce from medium and small farms.

This most recent paro nacional is thus the culmination of years of protesting against neoliberal policy, made worse by the economic repercussions of the pandemic. The ten demands of CONAIE reflect issues that have been compounded over time in Ecuador across different presidential administrations. They are not unique to the current presidency, but Lasso’s policies have certainly exacerbated the situation.

In this context, it is not surprising that by the second week of the June 2022 strike, the discourse shifted from the original 10 demands to “fuera lasso,” or calling for the removal of the president.

“Fuera Lasso” graffiti in the center of Latacunga. (Photo courtesy of the author.)

This call from the people to remove the president prompted the National Assembly (Ecuador’s legislative body) to begin the “muerte cruzada” process, which is similar to the impeachment process in the US. In this process, a 2/3 majority vote in the assembly is needed to revoke the president, and this process can only happen once in the first three years of a presidential term.

A repressive response

During the first week of the strike, the situation intensified quickly when CONAIE leader Iza was arrested on Tuesday, June 14 in Cotopaxi province under suspicion of “sabotage.” In Latacunga, the provincial capital, protests immediately surged in response to his arrest. Protestors demanded that he be released and claimed his arrest to be unlawful because he was detained through use of illegitimate force and without proper warrant or due explanation.

Protests in Latacunga, Ecuador, on June 14, 2022, in response to the arrest of Leonidas Iza, the leader of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE).

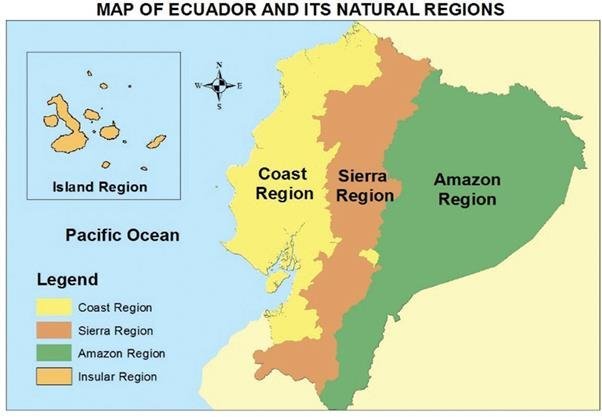

Iza was released on parole one day later; however, protests continued to grow throughout the week. On June 18, President Lasso ordered a State of Emergency or “Estado de Excepción,” in three provinces (Pinchincha, Cotopaxi, and Ibarra) where the bulk of the protests were taking place. The order was expanded on June 21 to three more provinces (Tungurahua, Chimborazo, and Pastaza) that constitute part of the Sierra and Amazon regions in Ecuador, where the majority of the Indigenous populations in Ecuador live.

Map of provinces of Ecuador (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Map delineating the three regions of ecuador - Coast, Sierra, Amazon. (Photo: Nataly Alejandra Paz/ResearchGate)

The State of Emergency placed a ban on public gatherings and authorized the use of force to suppress protests. This extreme measure took away Ecuadorians’ constitutional right to assembly and essentially criminalized any form of protest. The demonstrators, however, defied the State of Emergency and continued protesting, resulting in a surge in violence during the second week of the strike.

This increased unrest was further fueled by the National Police’s raiding of the Casa de la Cultura in Quito on June 19. This cultural center has historically served as a shelter and meeting space for indigneous protesters during previous national strikes. The raid represented a further attack on protesters’ rights and prompted Iza to declare that CONAIE would not participate in a dialogue with Lasso until the State of Emergency was lifted and the Casa de la Cultura returned to the people.

Pressure generates results

On June 23, Lasso ordered the military to return La Casa de la Cultura to CONAIE. Two days later, he ended the State of Emergency. These concessions appeared to be in response to the enactment of the muerte cruzada process. On June 26, while the assembly was debating the muerte cruzada, Lasso announced that he would lower gas prices by 10 cents a gallon. He had also previously proposed subsidies on fertilizer and other farm products, but CONAIE declared that these proposals were not enough and that Lasso also needed to address all 10 demands.

The following Tuesday, June 28, the assembly vote on the muerte cruzada was 12 votes shy of the 92 needed to achieve a 2/3 majority, so Lasso was not removed. Throughout the day, life in Latacunga slowly seemed to be going back to normal. There were more people out walking around the city, and more stores were opened. I was really starting to think that the paro was coming to an end.

Around 5:00 that afternoon, however, I heard that Lasso had refused to attend the scheduled dialogue with CONAIE because a soldier was killed during a confrontation with protesters and the military in Sucumbios, a province in the northeastern corner of the country along the Colombian border. Lasso’s refusal to attend the dialogue was largely hypocritical because several Indigenous protesters had previously died the previous week during confrontations with the military and police due to the authorized use of force. This, of course, further escalated tensions and heightened mass mobilization of Indigenous communities.

In Latacunga, we were told that stores would be open until 12:00pm on Wednesday, June 29, and then everything would fully shut down in response to the augmented fervor of demonstrators. On Wednesday morning there were lines outside of stores, and grocery store shelves were nearly empty. I felt like I had been transported back to March 2020, and I really did not anticipate Lasso agreeing to dialogue again anytime soon, especially after he declared yet another State of Emergency on June 29.

Return to dialogue and an end to the paro

Much to my surprise, on the evening of the 29th, Lasso confirmed that he would reopen the dialogue with CONAIE, and Iza also agreed to participate. The dialogue, mediated by the Episcopal Conference of Ecuador (the highest body of the Catholic Church), began on June 30 and will continue for 90 days, allowing the government time to engage in sustained discussions with CONAIE and follow through on promises made.

Here is a list of some of the agreements that were made between Lasso and CONAIE on June 30 (see also this summary in English):

Reduction of the price of gas by $0.15 per gallon

Commitment to repealing the State of Emergency

Repeal of Decree 95, which had increased oil production in Indigenous territories

Reformation of Decree 151, related to mining activity in indiengous and environmentally protected areas. This reform is expected to require the government to consult with indiegnous communities before mining projects are implemented in their territories.

Implementation of price controls for essential products/basic needs

Compensatory measures for the agricultural sector

Declaration of an emergency in the health sector

Debt forgiveness measures

Increased funding for Bilingual Intercultural Education

Reflections of a US citizen in Ecuador

I am hopeful that these agreements and continued dialogue will lead to impactful and long awaited change for the Indigenous and other disenfranchised communities of Ecuador. Needless to say, as a US citizen, I am impressed by the power of grassroots mobilization that I witnessed here in Ecuador during the past three weeks. Although I have seen mass mobilization in the US lead to tangible change, especially following the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, the sheer size of the US makes it hard to imagine a complete shutdown of the country.

I found it amazing that in Ecuador, the entire country was almost forced to be attentive to the grievances of the Indigenous communities, whereas in the US it is easier to turn a blind eye and ignore any political unrest because we are not always as directly affected by it in the same way that civilians are in Ecuador. Being here during the national strike forced me to learn so much more than I otherwise would have about the powerful Indigenous communities of Ecuador and how the government time and time again has failed to acknowledge and address their needs.

Furthermore, living through this experience reminded me about the power of people to enact change and influence policy at the national level. This has left me with a beacon of hope for the potential to overcome some of the recent threats to democracy at home in the US.

Establishment media coverage

Until the second week of the protests, I did not see any coverage of the strike by US establishment media, although Al Jazeera did report on Leonidas Iza’s arrest. I first noticed that the Washington Post began covering the story on June 21 and has since been continuing to report on the situation as well as the resolutions made. The New York Times only reported once on the strike on June 23 and has not continued the coverage. The NYT article primarily focused on the strike events happening in the capital, Quito, rather than other parts of Ecuador. Other than Quito, the NYT article only mentioned Puyo, a small town in the Amazon region, but only referred to the violence that had ensued there.

The establishment media coverage also did not thoroughly explain the history and context behind the strike. Independent media outlets such as People’s Dispatch, which I have linked several times in this post, provided more layers of context.

While it is not surprising that establishment media outlets largely failed to cover the events of the national strike in Ecuador, I think it is imperative that US citizens have access to thorough coverage on stories like this. The lack of mainstream coverage makes independent media coverage all the more crucial. Historically, the US has been deeply intertwined with the neoliberal policies that have restructured many Latin American countries at the expense of Indigenous communities. US citizens need to be able to learn about this history and to understand their country’s influence in the political and social unrest that countries like Ecuador, and even more recently Peru, have been experiencing.

Additional resources about the Ecuadorian National Strike

Interview with CONAIE’s Director of International Relations:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MT4DWkJE2h4

Further context and analysis:

https://www.rethinkpolitics.org/ecuador_strike/

Donations from our supporters allow us to continue training and publishing the work of our grassroots journalists. You can make a recurring or one-time donation at https://givebutter.com/weavenewsnow.