Chueca: Between Rainbow Capitalism and Fascism

The first time I visited the neighborhood of Chueca via the Madrid Metro system, I knew right away that I had gotten off at the right stop. Every wall in the Chueca Metro station is plastered with the rainbow print of the LGBTQ+ flag, as is the Metro station plaque marking the entrance on the street above. Chueca has been known as Madrid’s gay neighborhood since the 1960s, although it was not solidified as a cornerstone of the global LGBTQ+ Pride movement until the end of the 1980s, following decades of being reputed as a shady neighborhood plagued with drug use and risky sex work.

A Legacy of Repression

Even many years later, Madrid’s official recognition of Chueca’s value and identity via public signage, among other things, is still significant. We mustn't forget that it has been less than 50 years since Spaniards lived under a brutal dictatorship, and that Spain is an incredibly young democracy. From 1939 to 1975, Spain endured dictator Francisco Franco’s fascist military regime, the long-lasting effects of which still reverberate in the country’s social and political spheres.

“There is much to be said about the performativity of the liberal factions’ ‘acceptance’ of queerness, and I couldn’t help but wonder if the rainbow Metro station walls serve as more of an appeal to tourists than a declaration of solidarity and justice.”

Queer folks, along with other minority groups, were actively persecuted by the government and suffered systemic violence during the Franco era. This explains why it was simply not possible for Chueca to explicitly embody tolerance and pride until after Spain finally began its transition to democracy in the ’80s. Today, Spanish society as a whole expresses the same degree of tolerance for queerness as the rest of the Western world, including its European neighbors and the United States.

Capitalizing on Pride

That being said, there is much to be said about the performativity of the liberal factions’ “acceptance” of queerness, and I couldn’t help but wonder if the rainbow Metro station walls serve as more of an appeal to tourists than a declaration of solidarity and justice. After all, other Metro stations are decorated according to their respective famed locations; the Retiro station’s walls, for example, boast photos of the greenery found in the city's famous Retiro park.

The rainbow flag is but one piece of evidence proving that Chueca, at times, veers into what has been termed by queer scholars as “rainbow capitalism” or “pinkwashing.” This entails an increasingly common practice where companies commodify queerness by reducing it to a trend they can “support” and capitalize upon. Each June during Pride Month, for example, more and more companies change their logos to rainbow colors and advertise limited-edition Pride themed products.

But do these campaigns actually make tangible contributions to ongoing social movements for gender equity and justice? Well, that’s the aspect of Pride that draws the most critique, because usually, the answer is no.

One of the most well-known characteristics of capitalism is that capitalism and sex make a great team, and sex certainly makes its presence known on the streets of Chueca. You can’t exit the Metro station without first encountering giant posters advertising penis enlargement treatments which feature young men baring their washboard abs. And one of the first shops you’ll see is “La Pollería” with its pastel pink facade and absurd phallus-shaped waffles which are sold daily to giggling tourists.

“The narrower, quirkier parts of the neighborhood are decorated with stickers, posters, murals, and political graffiti, whereas on the streets most congested with boutiques and restaurants, blank walls can be found stenciled with the message ‘It is prohibited to put up posters. The advertising business will be held responsible.’”

As I passed sleek, brightly lit sex shops, vegan grocery stores, and overpriced bares de copa while on a walk through the neighborhood, I got the sense that most of these businesses target not only their queer-identifying neighbors, but also (and especially) “outsiders” who visit Chueca perhaps mostly for its novelty.

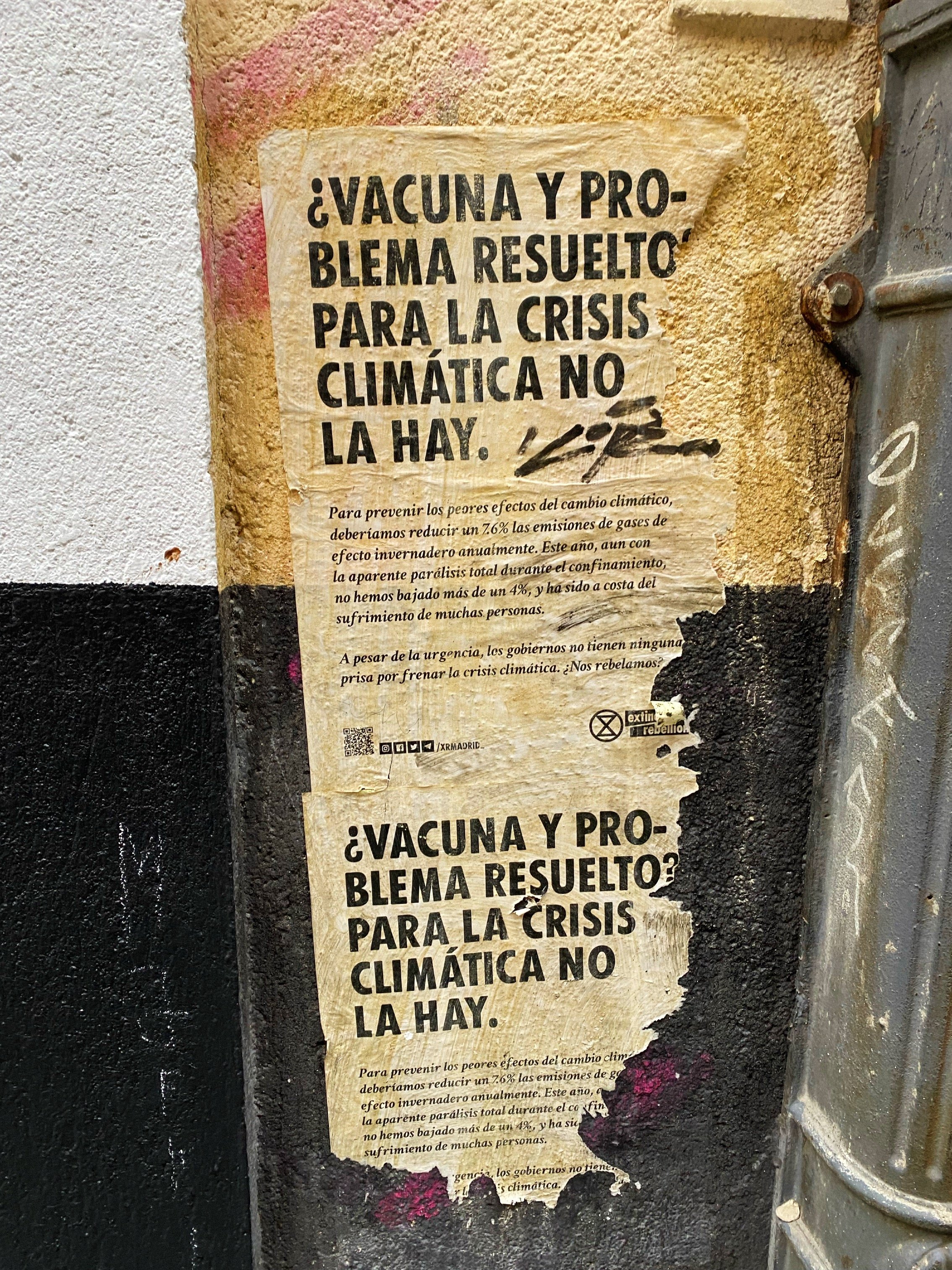

The remnants of two Extinction Rebellion posters. The bold text reads, “Vaccine and problem solved? For the climate crisis, there isn’t one.”

A small sample of the many stickers to be found on Chueca’s walls.

“It is prohibited to put up posters. The advertising business will be held responsible.”

Two Chuecas?

Even on a cloudy and damp weekday afternoon, tourists in the streets can be heard speaking French or asking directions to Gran Vía. This is in part facilitated by Chueca’s proximity to both the center of Madrid and the trendy “hipster” neighborhood Malasaña, and I have observed that the atmosphere does turn a bit grittier and a bit less censored the further you venture away from El Centro and toward the heart of Chueca.

“For those living outside of Europe, it might come as a surprise that a neo-Nazi march took place in Chueca just a couple of months ago in September. It received hardly any mainstream news coverage in the United States. The participants of the march, or rather, attack, carried flags and gear marked with far-right political symbols, denounced migrants, announced their support of Francoist nationalism, and made the Nazi ‘Heil Hitler’ gesture in addition to chanting homophobic slurs and threats.”

The narrower, quirkier parts of the neighborhood are decorated with stickers, posters, murals, and political graffiti, whereas on the streets most congested with boutiques and restaurants, blank walls can be found stenciled with the message “It is prohibited to put up posters. The advertising business will be held responsible.”

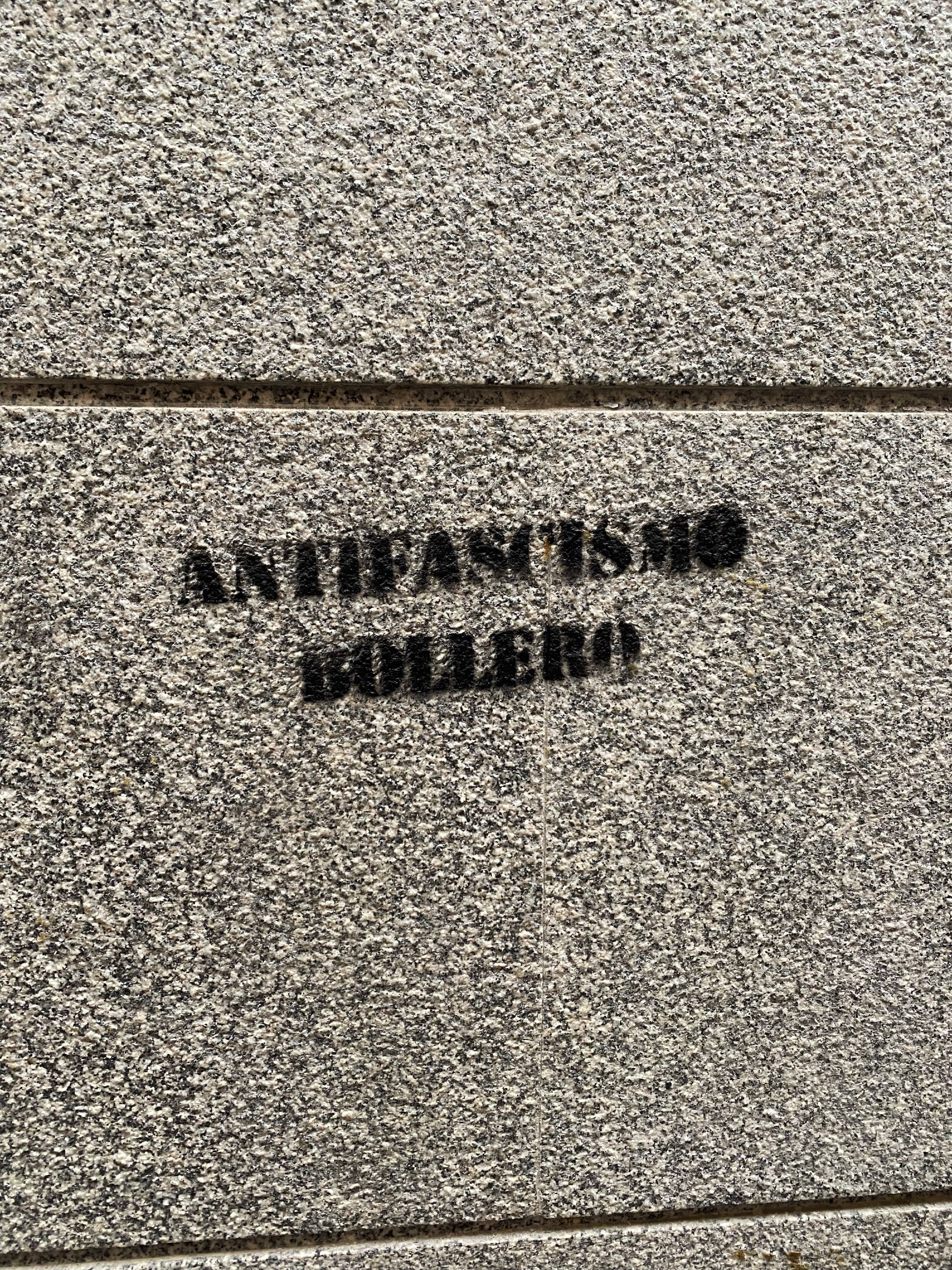

“Gay anti-fascism.” The Spanish word “bollero” directly translates to “baker” or “pastry chef,” but it is also used as a slang term for gay/lesbian/queer.

Mural by Swiss street art group NEVERCREW, created for the Urvanity Art International New Contemporary Art Fair in 2020.

The tensions underlying Chueca’s role in the Spanish political and social arenas have intensified during recent years, and so has the discourse surrounding them. Many activists and scholars have taken to the realm of academia to make their critiques. There is the late Spanish activist and drag queen Shangay Lily’s book Adiós, Chueca, which was posthumously published in 2016, as well as Ignacio Elpidio Domínguez Ruiz’s investigation of the far-reaching effects of 2017’s World Pride event, Se vende diversidad. In addition to formal critiques, alive in the streets themselves is a certain dissonance between Chueca’s curated superficial image and the more complex tensions of Madrid’s current social realities.

Fascism on the Rise

For those living outside of Europe, it might come as a surprise that a neo-Nazi march took place in Chueca just a couple of months ago in September. It received hardly any mainstream news coverage in the United States. The participants of the march, or rather, attack, carried flags and gear marked with far-right political symbols, denounced migrants, announced their support of Francoist nationalism, and made the Nazi “Heil Hitler” gesture in addition to chanting homophobic slurs and threats.

This jarring and violent attack has, perhaps, shattered a certain illusion of safety for queer folks and allies in Madrid. One of several harsh but crucial realities that have been revealed in turn is that the mere image of an expensive and stylish gay neighborhood aligned with Madrid’s liberal political faction was not, and cannot be, enough to stifle the steady emboldening of far-right ideologies and movements in the Western world.

Note: All Spanish texts have been translated by the author. All photos are courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.