Dissecting Boston X: Projected Other

Once again, borders become personal. In the previous blogs posts, I discussed the borders that partitioned Plum Island, Massachusetts. By exploring the archival documents, I stitched together an image of a divided sandbar, sliced up by the boundaries of private/public property. While this process mirrors the systematic division that has redrawn many New England communities throughout the centuries, Plum Island is unique in that it is emblematic of a human habitation where borders are sustained and destroyed by both economic and natural tides. In my previous dissections of Plum Island’s commodified territories, I focused on several elements that best illustrated this divisive process. There are many more stories and battles for property that shaped this barrier Island.

I will take a break from narrating these historical facts and focus on a personal matter. In this post, I will lay bare the process through which I have been interpolated into the surrounding borderlands. I have lived on the Island for the past eight months. My body, ethnicity and identity have become part of its fragmented terrain. To illustrate this personal case study, I conducted a series of rebellious/artistic acts on Plum Island and the city of Newburyport. Borders don’t only separate us from the other, they also cross our skin, turning us into the aliens of our own identity.

You Have an Accent

The events that brought me to live on Plum Island can only be described as a process of reverse gentrification. As stated in a previous blog, the exorbitant cost of living in Boston lead my partner and I to leave a community where we were acting as agents of gentrification. We previously lived in Dorchester, the largest and most populous neighborhood in Boston. We moved there in search of a place where we could live as working graduate students. In doing so, we entered a community where we were viewed as affluent invaders. Dorchester is the “New World” of Boston real estate. We were the beginning of the end, soon to be followed by exorbitant rentals and the influx of a wealthy (and mostly white) population. Those rent prices drove us away, in search of the cheapest place to live in commuting distance of Boston. That was how we found Plum Island and a winter rental that was cheaper than any apartment in the greater Boston area.

Commuting from Plum Island to Boston soon proved to be unbearable. We were stranded on the Island, an island which for centuries has given refuge to shipwrecked sailors. I quit my NGO job in Boston and I started working in a bread store in downtown Newburyport. My job was to slice, smile and hand out luxury bread to wealthy customers. It was here, at my place of employment, that my name and my ethnicity underwent the violent process of border projection.

Bread that is bagged to be donated (or thrown away) at the bread shop in Newburyport, MA.

At first, I was labelled with a mandatory name tag. It read “Tzintzun.” Thus began the marathon of explaining the origin and ethnicity of my name. The label read other, an exotic price tag. Their first thought was that I was Asian. They couldn’t believe I was Mexican. My customers were primarily white New Englanders. My name served as a mask, a mask where they projected both their fears and pleasant fantasies of Mexico. I soon stopped wearing my name tag. Then my accent gave me away, my white mask already fooling most of our customers. “You have an accent, where are you from?” became a mantra that was repeated throughout the day. “Oh, you are Mexican. Don’t worry, I don’t agree with Trump. I like Mexicans.” I started lying, make up boring stories about my origins. They kept asking about my name. I kept explaining. They kept masking. I kept lying. Personal borderlines can cut deep, the scars unfading.

Split Mexican Signifier

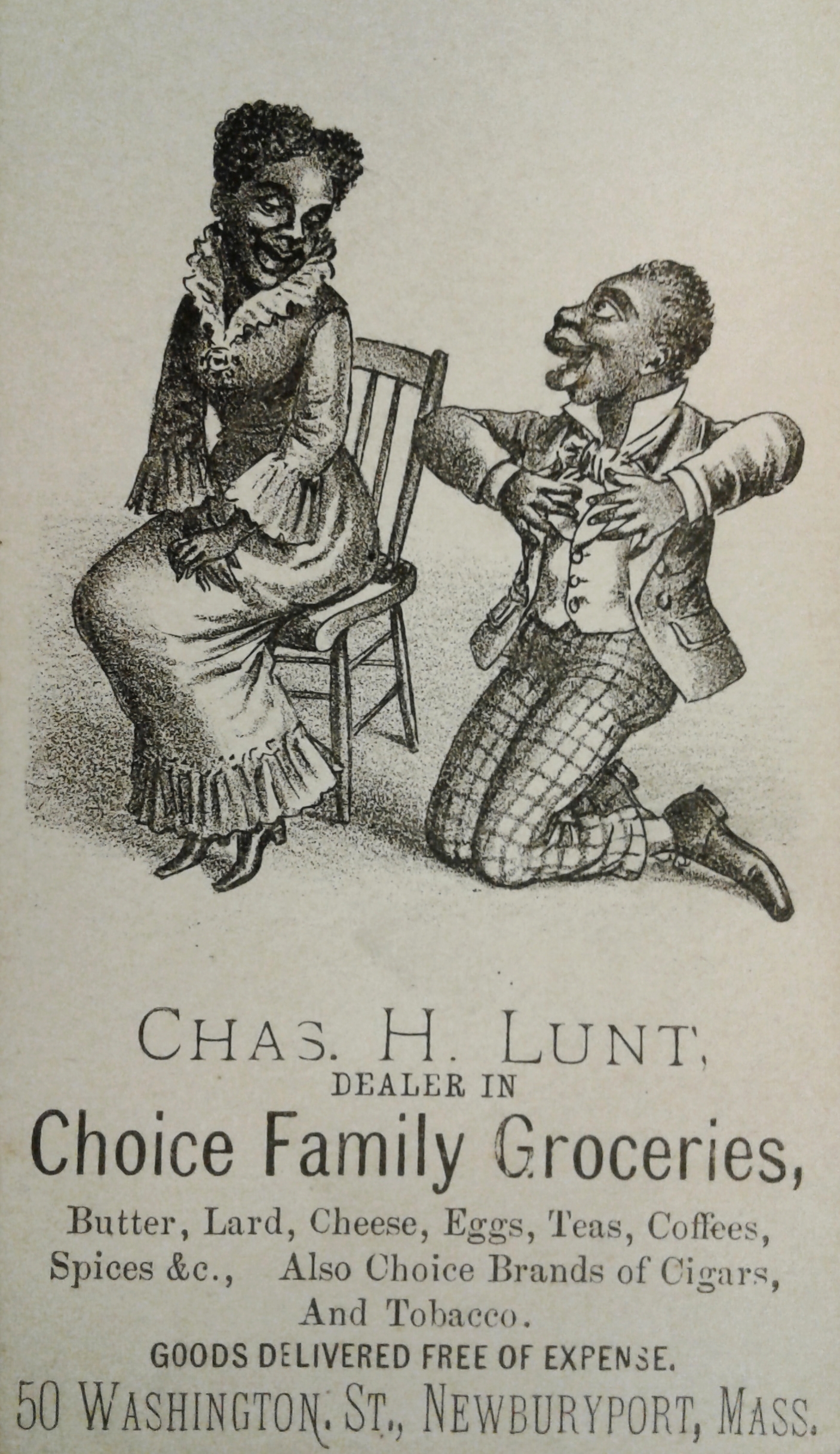

That is how I became their Mexican. The nice “boy” who gave them free bread at the end of the night. I was their other. My identity was thus commodifiable. Their projected image of me was, after all, their projection. Masks are a tool of differentiation. Through the process of masking one is interpolated, placed as an Other in the framework of society (Bhabha 44). The difference is then reduced to a superficial signifier, the flattened plane of a color. In my case, this color was imaginary, a projected image of the spectacle of Mexican identity. The writer and psychologist, Franz Fanon, analyzed this very process, the displacement from person to signifier, from individual to color, in the interpolation of the “Black Face” in French culture. While my own experiences are distanced temporarily by time and geography from Fanon’s case studies, both processes bare eerie similarities. Fanon uses Hagel as a starting point, and encapsulates this visual difference as an act of “being for the other” (Fanon 109).

"Choice Family Groceries" Business Card, Newburyport Public Library Archival Center, Newburyport, MA.

The ontological definition of an individual lies at the base of masked identification. For Fanon this process is complicated by the “jagged testimony of colonial dislocation, its displacement of time and person,” and “its defilement of culture and territory (…)” (Bhabha 41). It is the white man's eyes, his gaze, which creates the Black Mask (or the Mexican Mask) of identity. This is a violently epistemological act, for the “white man's eyes break up the black man's body,” trim it, and place it within their frame of reality (Bhabha 42).

This disturbance is an act of scission, the division between reality and its representation, between the projected image and the erased object. The “demand and desire” of the colonialist gaze “is a space of splitting” (44). Yet one is not left with a “neat division” between mask and skin (44). The colonial gaze highlights this voracity through the “disturbing distance in-between” Self and Other: the “whiteman’s artifice inscribed on the blackman's body” (45). It is thus “the production of the image of identity” that shapes the reality of those who wear the mask and assume the image (45). The mask brings the subject in question to “ask himself if he is indeed a man,” for “his reality as a man has been challenged” (Fanon 98). Through this complex web of identity signifiers, the black body is dissected; “dissected under white eyes, the only real ones” (116).

My identity as a Mexican was thus caught in a fetishistic reflection, the images projected onto the minds of gazers, reflected onto the black slate of my smile. I was the rapist, I was the alien, I was the vacation, all rolled together in a $1 burrito special. I was the substitute, the shadows that encapsulated “the 'fantasy (as desire, defense) of that position of mastery” (82). My Mexican ethnicity was a screen. I was split by their projection. The holders of sight split their gaze, the president’s words ringing in heads swimming in the Cinco de Mayo margarita special. When I said, “I am Mexican,” I became an object, viral signifier, split by the invisible border-play “of need and desire (…)” (82).

Even though New England is considered a center of resistance against the xenophobia of the current administration, its history is written in division. From colonial fences to gentrified communities, borders scratch lines in the mask of New England identity. The image of the revolutionary “Patriot” still permeates New England culture and is the bedrock of the Yankee identity. Returning to David Chauncey Brewer’s racist manifesto, the “Yankee stock” were the rightful inhabitants of New England (Brewer 23). The Native American’s were justly exterminated and robbed of their land, for they “had not dreamed of the treasures that lay within call of the men who were brave enough to face apparent adversity in this district” (21). The mask of Yankee puritan culture, the rightful owners of their “promised land,” were placed in contrast with the “invading armies” that moved so swiftly that record shows them to have been in full military occupation of the penetrated country in an exceedingly short space after crossing the border” (150).

One of our more recent "Colonizers," eating a taco taco bowl. He probably would have gotten along splendid with the first European hogg inhabitants of Plum Island. The first hoggs were eventually evicted from the Island, due to their over-consumption and inconvinient tendency to provoke erosion.

Brewer’s analysis mirrors the campaign rhetoric of the current administration, as well as most contemporary xenophobic discourse. In the face of the “alien invasion” Brewer longed for “the awful imminence of impending doom such as threatens the race that built classic New England to wake creative power in the human” (369). The reality TV show president, though he is not a Brewer Yankee, has placed himself in the role of “such a manifestation” (369). Mexicans and Muslims became the signifiers, masks, that the now president has sought to divide, one tweet at a time, the “darkening shadows” of the Mexican invasion galvanizing and frightening the American electorate. Before and after the election, whenever I mentioned my Mexican heritage, I was immediately cast in the mask of the #rapists. Despite the fact that most people disagreed with that label, it has become ingrained in the Mexican chain of signifiers. There is no way of escaping the mask of the “bad hombre.” The only way such a label could go viral, was that the Mexican identity had already been turned into a signifier, a typification. To be Mexican was wearing a sombrero and embodying a restaurant. Being a rapist wasn’t that much different from being a taco.

The Taco Truck

A taco truck has appeared on the Plum Island Turnpike. Since 2014, the taco truck has become an essential part of the Plum Island experience. Parked in the parking lot of the Plum Island Airport, the truck serves tacos to the hungry New England tourist. The food truck has received stellar reviews from the Boston Globe and other local newspapers. In past years, its brand was a Mexican sombrero, its backdrop, ocean waves. The owner and the costumers of the food truck are not Mexican. The Mexican cuisine and its image was part of a branding scheme. The owner had previously considered opening a steak food truck, but then decided to go with a flavor that would be “most popular.” This past year, the food truck has been repaired and “rebranded.” The sombrero has been replaced with a fist holding a taco. The fist is reminiscent of activist stencils. The symbol of socialists and social resistance has been coopted to sell Mexican food. The food truck’s new slogan is: “Join the Taco Revolution.”

The signifiers of protest and Mexican identity are for sale on the Plum Island Turnpike. They are used as branding mechanisms, masking the food truck’s image. These are the masks that are twisted, projected. I am cast within the masks that people have already seen. My ethnicity has been stolen by a food truck and my very acts of resistance are an incentive for consumption. Cultures can be foodified just as easily as they can be dehumanized. In both cases, the culture is consumable. Racism comes in all shapes and flavors. Hard shell or soft shell, anyone?

This game of signifiers is a slippery process. It is on this borderline where I slip from food truck to an invasive army of gangsters. When you don’t see me (and you project your fantasy) you are complicit in the violence of masking. There is a very thin, liquid membrane between the different border masks of misrepresentation. Between a restaurant and rapist, you forget to look at me. It is not a coincidence that the current president was elected into office. He is president of a society that projects spectacles to control their others, masking their desires and their fears.

I placed a sticker on the Plum Island food truck: black and white covering its new shinny yellow surface. The small letters act as a call for attention. It is a personal statement, my act of rebellion.

I AM MEXICAN: DOES THAT MEAN I AM RAPIST OR A RESTAURANT?

"I AM MEXICAN: DOES THAT MEAN I AM A RAPIST OR A RESTAURANT?" Sticker, Placed on Food Truck, Plum Island Airport, Newbury, MA.

Works Cited

Bhabha, Homi K., The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994. Print.

Brewer, Daniel C. The Conquest of New England by the Immigrant. New York & London: The Kinkerbocker Press, 1926. Print.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. 3rd ed. New York: Evergreen Black Cat, 1968. Print.