Dissecting Boston II: Lines of Complicity

Introduction

In the following blog post, I will explore the balancing act of being complicit in the borders that ensnare our actuality. To accomplish this task, I will first discuss how the restrictions of gentrification mirror the larger walls being cemented around American identity. Donald J. Trump, the focus of most of Wall creation discourse, is himself a symptom of a much larger separation. These separations follow the guidelines of spectacle, and the social media platforms that have monopolized our means of communication. While the president is an extreme example of this process, we are all complicit in this division. We are, consciously or unconsciously, ensnared in a system that gentrifies, splits communities, and realities. I use my presence as an “agent of gentrification” as a case study of this process. Finally, I will employ my protest/street art piece, “The Great Boston Wall of Gentrification” as an example of how we all could become more conscious of the walls that surround our lives and take action to unearth their very foundations.

By Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo

Divided Boston, Divided Nation

Walk down the streets of Boston, and one becomes aware of the lines that segment the city. In the face of globalization and overzealous capitalism, the facade of one of America’s oldest cities is rapidly morphing. The invasion is being undertaken street by street, shattering the cultural fabric of Boston. This depiction may at first appear eerily familiar to the xenophobic rhetoric of the current administration. While most people who currently live in Boston are caught in the tide of this exclusionary process, they aren’t the direct culprits of this transformation. The invaders are a conglomeration of forces shaped by real estate capital and investment. Trump himself, as well as his family’s legacy, are emblematic of this process. For decades, the Trump family has reshaped New York City in a dangerous game of real world monopoly. The players in Boston’s game board aren’t as visible as our “unpresidented” president. They are hidden in the shadows of economic development, silently drawing borders, subdividing and secluding individuals along class and ethnic lines.

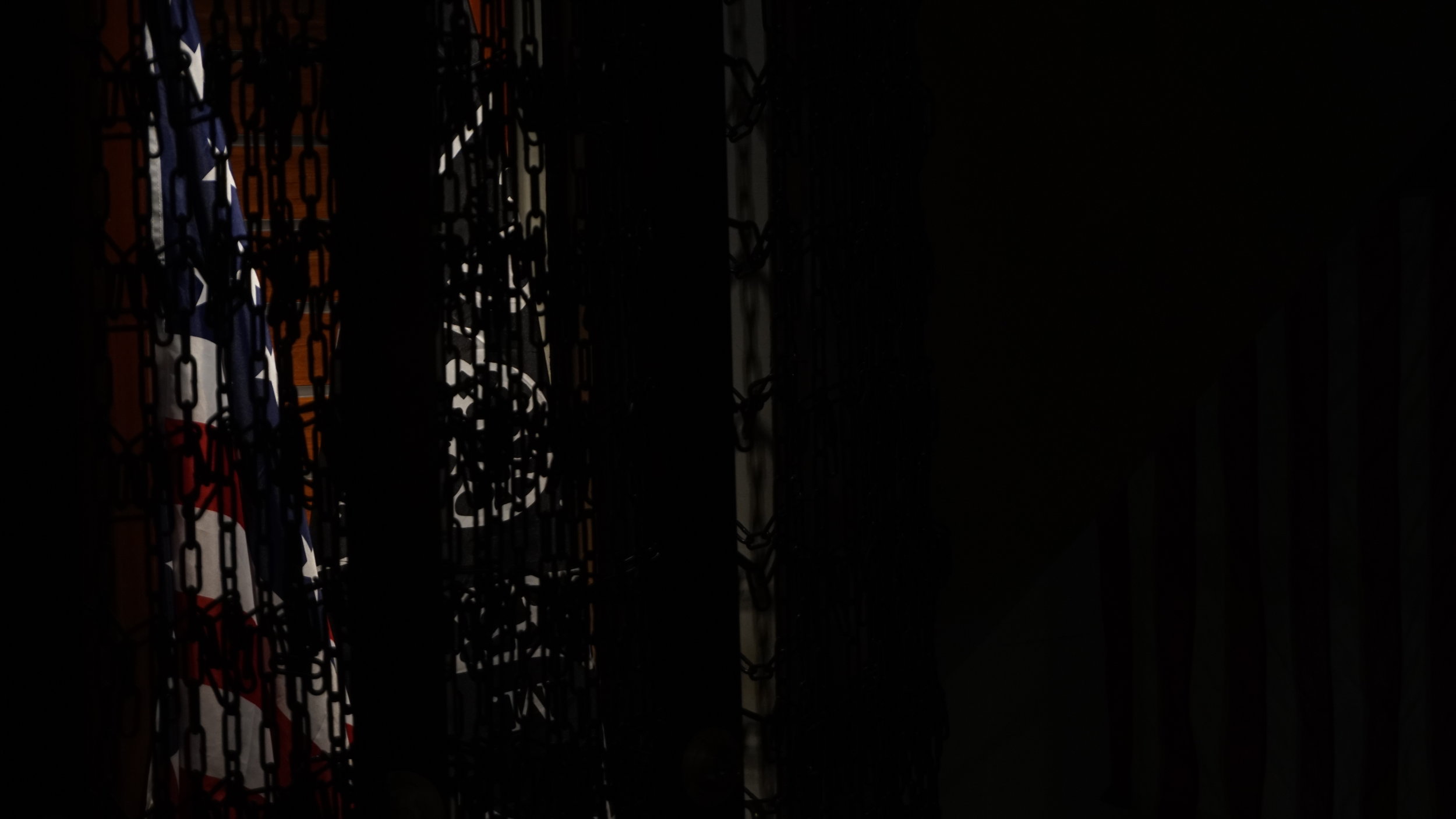

Throughout this spangled U.S.A, borders are being erected, strengthened. The act of building walls between individuals, nationalities, cultures, and realities is a flash point in contemporary discourse. Exclusion is trendy, a newly growing fashion. The current administration uses walls as its go to punch line. They set the stage of a sitcom colosseum, a colosseum in which millions of people become the play things of spectacle politics. These shock events swamp the national newspeak. While people rally behind, in front and against these borders, the nation slips slowly toward a postapocaliptic/postcalipitalistic oligarchy. The distracting images of division, like all forms of spectacle, have disastrous and violent consequences.

"Spangled Borders" by Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo

The Spectacular Language of Separation

It is hard to deny that Donald J. Trump is the president of spectacle. The situations artist Guy Debord defined spectacle as “capital to such a degree of accumulation that it becomes an image” (Debord, 1967). The image that has bombarded the public across all media platforms is the spectacle of Donald Trump. The president is a viral signifier, spectacular commodity, entrapped in a society “where modern conditions of production prevail” and “all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles” (Debord). Social media, the president’s preferred means of communication, is a direct example of a space where “everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation” (Debord).

This process can be deceiving, for all falsehoods, illusions, conceal dangerously shifting tides of structural violence. The spectacular borders that are currently being raised seek to outline a universal vision of American identity. However, “the unification it [spectacle] achieves is nothing but an official language of generalized separation” (Debord). On the @realDonaldtrump’s twitter feed, separation is the mask of his presidency. The act of creating a spectacle is itself a partition between reality and its representation, the differentiation between a signifier and its object.

All spectacle contains falsehood, but recently these “lies” have been enthroned, employed to establish the circumference of American Identity. This perimeter is drawn by difference. On both sides of the wall masks are being donned. To be American, or un-American, are now both forms of spectacle. In contradicting Trump’s rhetoric, it is easy to adopt the same spectacular language (written in 140 characters). In contradicting spectacle with spectacle, are those who stand against the current administration also complicit in the divisions that fracture contemporary society?

Being Complicit in Separation

To illustrate how it is uncannily simple to become complicit in spectacular separation, I will narrate my own personal experience as a foreign invader, an agent of gentrification. The very term “gentrification, or the perception thereof, has been a source of conflict, confusion, and seemingly competing value system for transitioning communities” (Stephanie Brown, 2014). When I moved to Boston to go to graduate school, I unknowingly “transitioned” into a city where the cost of living was rapidly shifting the city’s topography. I was thus caught, like the long-term inhabitants of my new community, in the constraining net of rapid and costly transformation. The way in which the fluid contours of gentrification engulfed me can serve as illustration of the blurry ramparts of complicity.

"Shifting Foundation" by Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo

I moved with my partner to Dorchester, Boston’s largest neighborhood. Certain segments of Boston’s population knew Dorchester to be a “sketchy” neighborhood (I quickly learned that “sketchy” is Boston’s term for non-anglo communities). Dorchester is on the verge of gentrification; the next community to be invaded, its low rent soon to be exploited. While I myself am Mexican American (possibly sketchy), I was also a student looking for a cheap place to live. Thus, it is undeniable that I was part of the first wave, a factor in the “transition.” While I had been warned that Boston was a “divided city,” I wasn’t prepared for the ever-shifting lines that divided the neighborhoods street by street. This process isn’t only relegated to the present day. Instead it can be traced back to Boston’s colonial past, and the borders erected around European private property in new conquered “New England.” In the end, I too was excluded by this historical transformation. My partner and I were forced, for financial reasons, to move more than an hour away from Boston proper, expelled by the forces with which we unknowingly colluded.

While living in Boston, I worked at a Community Based Organization in Mission Hill, a borderline community neighborhood between the university spotted Fenway, the gentrifyingly hip Jamaica Plain and the more impoverished Roxbury. While many of the youth I taught didn’t know the meaning of the world gentrification, their families were finding it increasingly difficult to live in Boston proper. The Community Based Organization was rapidly finding itself without a community. The rents in Mission Hill were skyrocketing, large development projects were slowly expanding, and college students (with loans or family money) were becoming the dominant population. One of my primary tasks as an employee of this CBO was to build relationships with the larger cultural institutions of Fenway. I thus found myself tripping over the invisible lines that divided the different segments of the Mission Hill community, and the unconscious (and economic) barriers erected by its residents.

In my most recent visit to Fenway and Mission Hill I outlined these boundaries, physically. With a string of yarn, I drew small borders, figuratively cutting an already divided community. In doing so, I acknowledged my own presence, as a representative of transition. Next to minimalistic acts of yarn bombing, I included a small label, titling the piece: “The Great Boston Wall of Gentrification.” The title alludes to the national discourse surrounding “wall building,” but it further focuses on the smaller, less noticeable wall that surrounds our every movement. While in a less flamboyant fashion then our current President, the way we move and speak (in the virtual and physical world) is a vital link in the walls that divide our globalized, classist and racist society. It is thus essential for all of us to come to terms with the walls we perpetrate, whether it is in our economic fingerprint, our social media presence, or our interpersonal conversations. Walls only exist if there is a society to sustain them. If the society rebels, rejecting the barrier’s foundation, walls will crumble.

"The Great Boston Wall of Gentrification (Ruggles Station)" by Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo

To be continued…

In the following blog posts, I will further explore the historical roots of “The Great Wall of Boston,” by dissecting the Puritan colonizer’s relationship with their new environmental reality (a relationship that lies at the foundation of the “American” conception of private property). I will disentangle the knots in the relationship between the spectacle of social media and the spectacle of Donald Trump (both perpetrators of the spectacle of American identity). But before I delve into the history, theory, and actuality of division, I will describe the artistic/activist method I undertake to further illustrate my larger statements. In the manifesto, I will elaborate on my art/activist practice and the ways in which people can use similar methods to dissect the walls surrounding their own lives. Dissecting the borders that weave together our reality is an intricate process, and it involves our collective effort and consciousness.

"The Great Boston Wall of Gentrification (Quincy Market)" by Tzintzun Aguilar-Izzo